Hà Nội: Vietnam National Fine Arts Museum & Lenin Park

(day one of my trip to Hà Nội, part two)

Thanks for visiting Narrative Nation!

I’ve returned to Vietnam for a solo adventure after walking the streets in my mind so many times since I first visited with the family in 2019. This trip includes the capital city Hà Nội; a homestay by Sông Lô (the Lo River) in Hà Giang, the country’s northernmost province bordering China; and a two-day motorbike ride on the famous Hà Giang loop. Because this is such a fascinating and exciting place, and especially because there is so much interesting patriotic and nationalist art and public history to consider in Hà Nội, I’m going to share some photos and short videos with a few captions here instead of keeping it all on my personal Facebook page. I may return to add more information to some of these later. Enjoy!

Welcome back to my trip to northern Vietnam! If you missed the first post including a walk through the Old Quarter, a stop at The Note coffee shop by Hoàn Kiếm Lake, and a visit to beautiful Văn Miếu, the 11th-century walled compound dedicated to the Confucian education system, and you can check it out here. This post covers the rest of my long first day with two more interesting and very different stops, one of which gets me thinking about some of the Vietnamese novels I’ve read in the last seven or eight years.

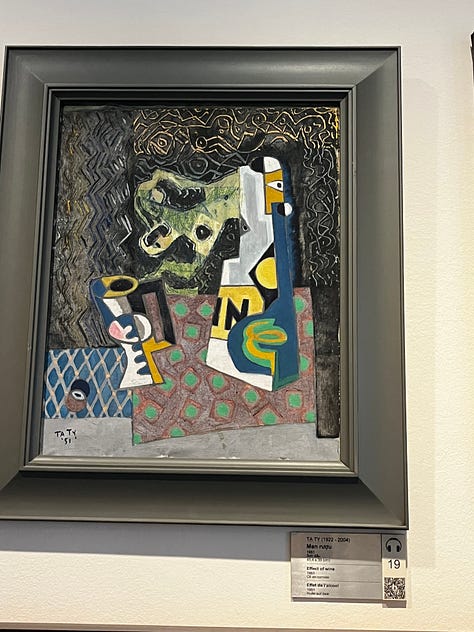

After leaving Văn Miếu, I walked about half a mile to the Vietnam National Fine Arts Museum. The museum occupies a French colonial building originally used as a boarding school for French officials’ daughters. In 1962, the Vietnamese government began converting the building, including the addition of some Vietnamese architectural features, and the museum was opened in 1966.

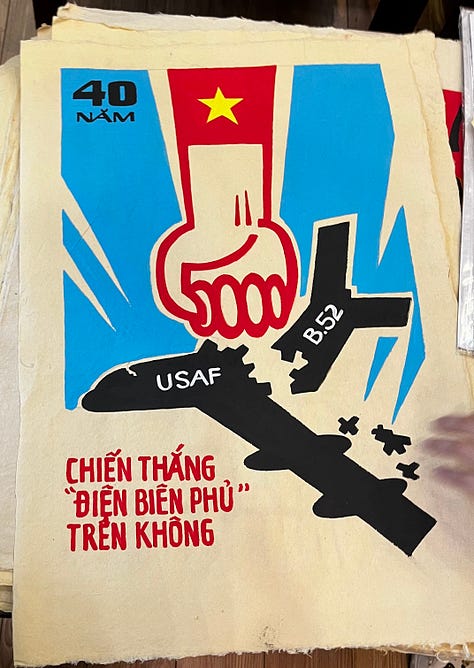

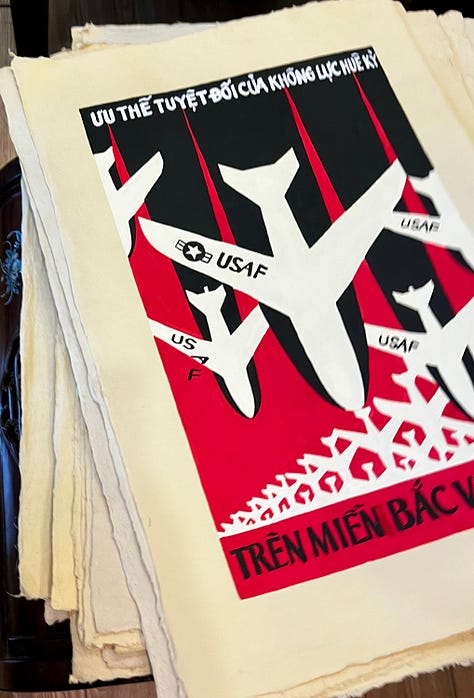

Several rooms emphasize the resistance to the French in the first half of the 20th century, war against American invaders in the 1960s and 70s, and the effort to reunify north and south during and after that time.

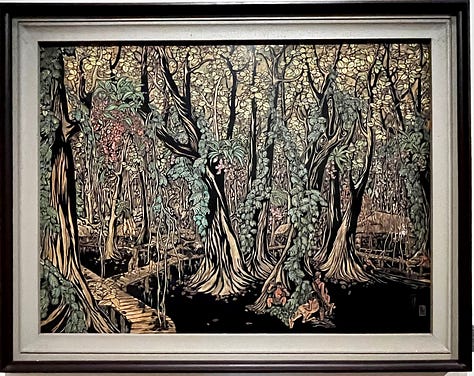

The three paintings above are among the museum’s many examples of the much respected and apparently very difficult technique of painting with lacquer. Using liquified natural lacquer was refined in the 1920s and is considered by the Vietnamese to be one of the most important developments in the nation’s pre-independence modern art.

The first two were produced near the end of the war with America: “Marching at Night” (1976) and “In the Mangrove” (1974). “In the Mangrove” looks at first to be more of a natural scene, but the largest human figure in the foreground carries a military rifle to clarify the artist’s true focus. The sacrifices of the Vietnamese in the long effort to unify their country under the leadership of Ho Chi Minh and the communist party are the central theme in much of the art and signage throughout the museum. The third painting, “Uncle Ho on a Military Campaign” was produced ten years later in 1985. Paintings with similar subjects through the early 2000s show the enduring importance of telling this story.

An hour in the galleries devoted to resistance and the war period presented me with a pretty clear message. Each of these representative works combines the distinctive painting technique that is a point of national pride with scenes of military life and Vietnam’s natural beauty. This three-pronged approach equates the sacrifice of soldiers fighting for the communist party with the highest and most enduring treasures of any nation, the distinctive and beautiful art and landscape. So this is simultaneously a form of nationalist propaganda and a form of beautiful art that, in both capacities, honors the connection between the individual and the country. This is my first take on it without investigating what I’m sure has been written about this fascinating but discomfiting tradition.

Here and in the women’s museum I will post about later, representations of the south focus only on those Vietnamese who resisted American forces and worked to unify the country under the communist party. I may have missed something, but in these state-controlled displays of public history, I saw no indication of the recrimination and imprisonment of south Vietnamese people after the war. A single tone resounded throughout these galleries, so naturally the narrative feels incomplete.

It’s intensely interesting and educational, though, because on the American side of this narrative warp, the perspective and language of the north Vietnamese during many decades of colonial resistance and civil war is still rarely heard. Yes, we learn in school and from the media, “[this] is what [they] thought.” That’s very different from seeing the narrative presented in their own words to their own audience. The emphasis throughout many artworks of the 1960s and 70s is on driving out the American invaders so the nation could be reunified, saying nothing of the many Vietnamese in the south who did not share that goal.

I’m not an art historian and don’t know where to find the paintings and sculpture telling that story. But I have read a good number of Vietnamese novels that acknowledge and explore the painful and often unreconciled spectrum of perspectives that existed in the complex, family-destroying decades of colonial resistance, civil war, foreign invasion, and the eventual reunification and rebuilding.

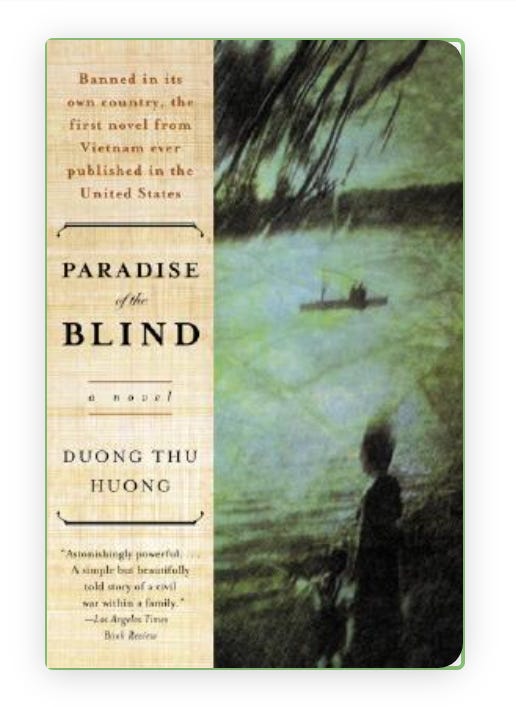

Many of such novels have been written, and they are popular, but they are also not easily permitted by the government. For example, Dương Thu Hương is one of the nation’s most popular writers. She volunteered in the women’s youth brigade during the war against the Americans in the late 1960s and again when Vietnam fought China at the border in 1979. But in spite of her service to the north Vietnamese government and the war efforts, she was imprisoned in 1989 and 1991 for her increasingly political critique of conditions in the north, and her novels have been effectively banned in the country.

Her 1988 Paradise of the Blind was the first Vietnamese novel sold in an English translation. Isn’t that hard to believe. Most of her book sales are in foreign translation, though some are smuggled back into the country. For years before moving to Paris in the mid-2000s, she lived under restriction. I’d like to research all of this a bit more, but that’s the general outline of her career as someone who has been labeled a “dissident writer.”

Another Vietnamese novel that moved me deeply with what I felt was an honest depiction of the disappointments, losses, and personal hardships following years in the NVA is Bao Ninh’s The Sorrow of War. In 1994, The Independent awarded the English translation the Best Foreign Book award, and it has been deemed the country’s bestselling novel. But these perspectives are not officially sanctioned because they do not present a uniformly positive view of the long and often violent effort to unify the country under Ho Chi Minh’s vision of communism. Thirty years later, Bao Ninh has just recently released a second book, Ha Noi at Midnight, a collection of ten stories set in and around the war.

But Vietnam’s history does not begin with the 19th-century French occupation, much less with the 20th-century communist party or the American war. The museum of national art also contains many gorgeous cultural artifacts from earlier periods.

The bottom row of photos in the set above is not from the museum but from an antique shop I visited while walking through the Hoan Kiem Lake neighborhood. The two on the bottom left show handmade wooden puppets from the traditional water puppet theater shows that enact Vietnamese folklore and mythology.

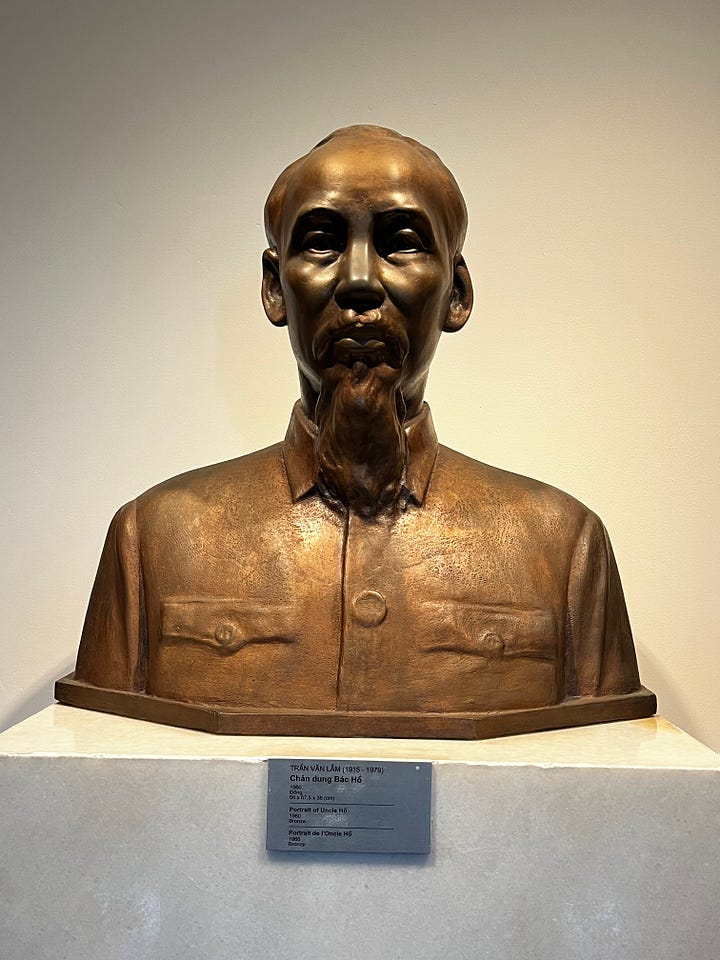

The bronze bust below, “Portrait of Uncle Ho,” was cast in 1960. The stone lion was part of the Ba Tam pagoda in Hà Nội, about 850 years earlier, ca. 1115. The two are not in the same gallery at the National Fine Arts Museum, but I’ve put them together in my own space here to create a larger sense of time as I breathe the air on this peninsula for the second time and look out my third story window into the quivering tops of trees that have grown here in the past, are growing here today, and will grow here again.

After leaving the museum with a lot to think about, I headed for Lenin Park. I knew the park has a large Lenin statue, but I didn’t know what else to expect. Approaching the area, I saw many banners for this week’s 70th anniversary of War Invalids and Martyrs' Day (July 27, 1947 - July 27, 2017) and several military transport vehicles along with armed guards in front of government buildings. The surrounding area was patrolled, landscaped, and decorated, but the park felt fairly neglected.

The shady side of Lenin Park was occupied almost exclusively by older men, most of whom were playing a complicated variant of chess called Cờ tư lệnh, or “commander chess.” The game draws crowds of commentators in nearly every park where it is commonly played on the ground with mats like the one shown here. It’s also sold in shops with a wooden board like international chess sets.

A man sat motionless beneath a tree in the center, and lots of dogs ran around playing and fighting. A burly dachshund patrolled the game and chased everyone off, including me. This side of the park was the most neglected of the public green spaces I’ve seen so far in the city in terms of plantings, trash pick up, and general maintenance.

The other side of the park was paved and exposed to the sun. Under a large bronze statue of Lenin holding his manifesto, younger men kicked a soccer ball and the even younger men rode bikes and skateboards. There were only one or two women around, including one transferring water and some other orange drink among several plastic bottles for reasons I couldn’t understand.

After watching the skaters for a while, I headed back over to the Old Quarter. Along the way I got a doner kebab-banh mì hybrid for 50,000 VND (about 2 USD) from a guy with a cart called Cafe Goethe. It was a lot better than it looks in this video because the bread and pickled cabbage were so good.

I also came across a scooter rigged for the end times, the most unofficial barbershop in town, and all the eggs, but thankfully not in one basket, being loaded up to be carried across town on a bike.

That’s enough for one photo blog, I’m sure! And I hope you forgive me for thinking through these national narratives, propaganda, and banned books. Obviously, the subject touches so much of what’s happening in the United States right now and menacing in the margins.

This is really great, Laura! As an American, one never really sees or hears about the Vietnamese government's perspective on the colonial era and the War. Really nice pictures of the museum artwork and stories of the dissident writers. The people my father worked with during the War were indigenous Hill tribe people who didn't really like any Vietnamese, north or south. But their history is a whole other story. There is an indigenous people's museum and park somewhere in Vietnam, perhaps Hanoi. Thank you for all your pictures and perspective.