Thanks for visiting Narrative Nation!

I’ve returned to Vietnam for a solo adventure after walking the streets in my mind so many times since I first visited with the family in 2019. This trip includes the capital city Hà Nội; a homestay by Sông Lô (the Lo River) in Hà Giang, the country’s northernmost province bordering China; and a two-day motorbike ride on the famous Hà Giang loop. Because this is such a fascinating and exciting place, and especially because there is so much interesting patriotic and nationalist art and public history to consider in Hà Nội, I’m going to share some photos and short videos with a few captions here instead of keeping it all on my personal Facebook page. I may return to add more information to some of these later. Enjoy!

Hà Nội walk with afternoon rainstorm

The Vietnamese Women’s Museum is just a few blocks south of Hoàn Kiếm Lake, in a somewhat less congested part of the city. It was starting to rain as I got closer, and by the time I reached the museum it was a lovely, soft but full rainstorm that I didn’t really mind getting caught in.

family

The museum’s entrance area features a statue representing the Vietnamese mother, one hand pushing down the struggles of life while the other holds up the child. And an accidental selfie, soaked from the walk, looking up to her.

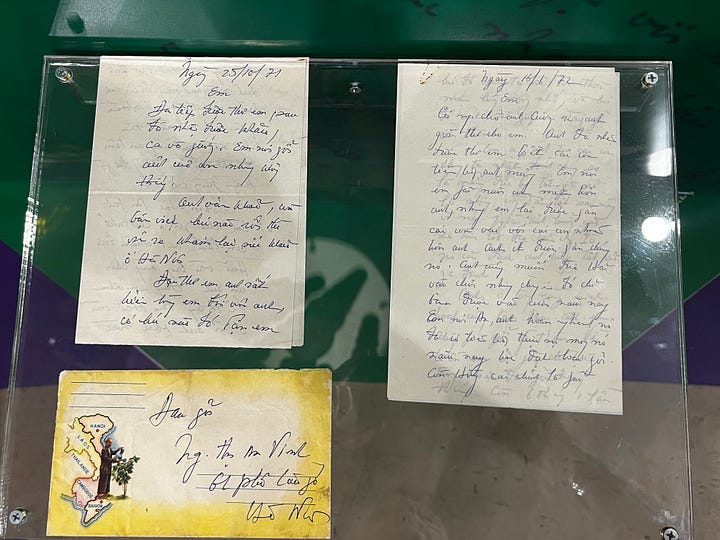

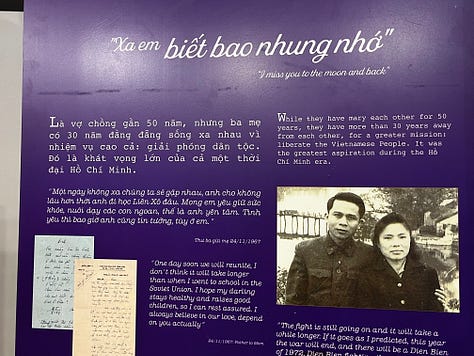

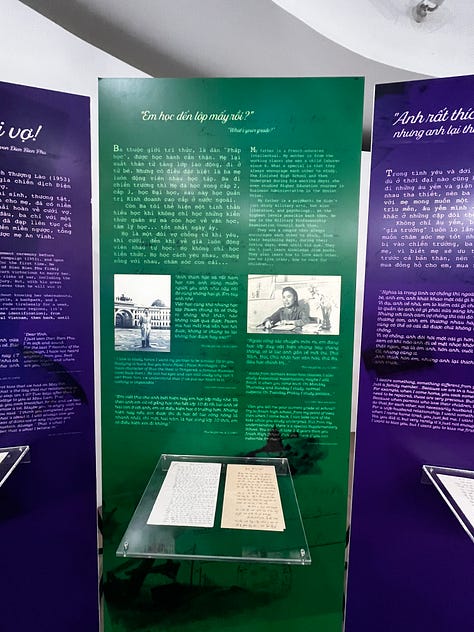

The featured exhibit in the lobby contains excerpts from the many collected letters of a couple who married young and had a child, but didn’t really get to live together for about 25 years. In a letter written after they had been apart for 18 years due to war, the husband refers to the anticipated victory over the Americans as “Dien Bien 1972,” suggesting that the repulsion of a foreign invader would mirror the nation’s defeat of French colonizers in 1954.

The selections presented in the exhibit are strictly patriotic and emphasize sacrifice for the nation and the role of the family in preparation for the next generation to inherit a unified country. The couple’s varied social status also presents an ideal for the communist nation: while he was an intellectual from the French education system, she had been a laborer since childhood. Together, they continue their own educations, while the husband encourages his wife to tend to the education and health of their children.

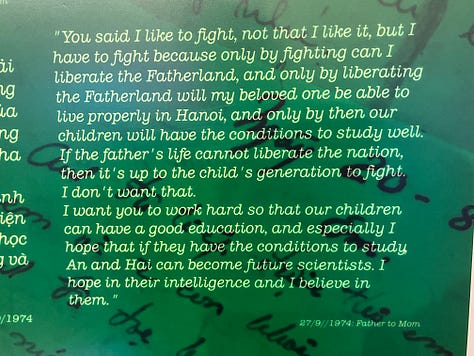

One of the letters from the husband:

“You said I like to fight, not that I like it, but I have to fight because only by fighting can I liberate the Fatherland, and only by liberating the Fatherland will my beloved one be able to live properly in Hanoi, and only by then our children will have the conditions to study well. [ . . . ]

If the father’s life cannot liberate the nation, then it’s up to the child’s generation to fight, I don’t want that.”

The next level of the museum looks at traditional childbirth and motherhood along with the modernization of pre- and postnatal care for Vietnamese women.

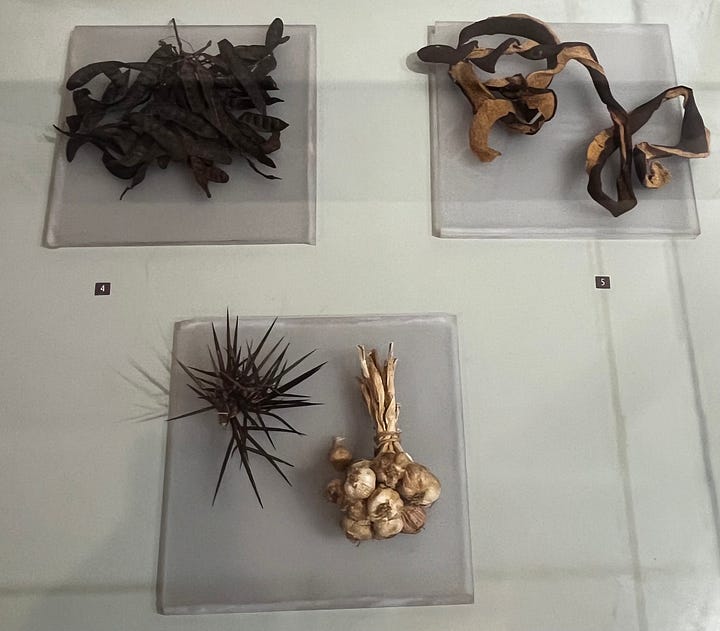

In Cham and central Viet families, grapefruit skins and February fruit chase away evil spirits and perfume the home for new mothers. The thorn of the February fruit and garlic ward off evil spirits at the entrance.

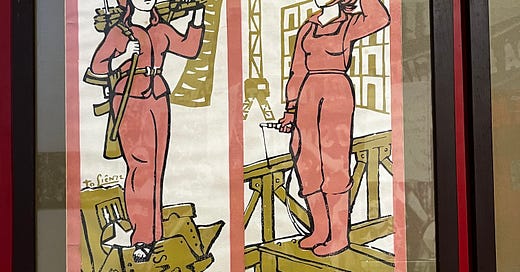

fighting for unification

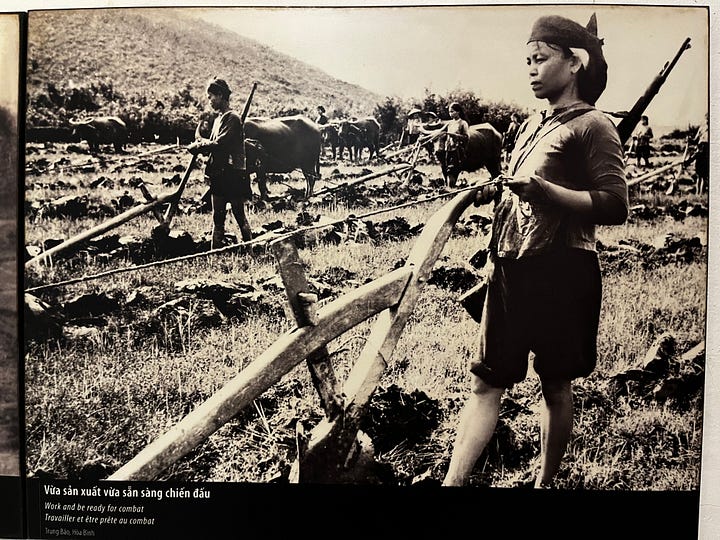

The central floor of the museum contains some fascinating artifacts and photographs from women’s (and in some cases girls’) involvement in the nation’s struggles for independence from foreign invaders and for reunification of North and South. As in the Vietnamese National Museum of Fine Arts I wrote about in an earlier post, the stories shown are limited to those who fought for the North.

The first photo below illustrates part of the “three responsibilities” movement for women during the war: to work and maintain their region’s agricultural production and to ready themselves for combat in defense of their locality. The third responsibility was to continue in the traditional role of household management.

These pictures show international efforts raising money to support Vietnamese women during the war. Japanese women sold handmade paper dolls, and a recording of Vietnamese folksongs was sold in Germany.

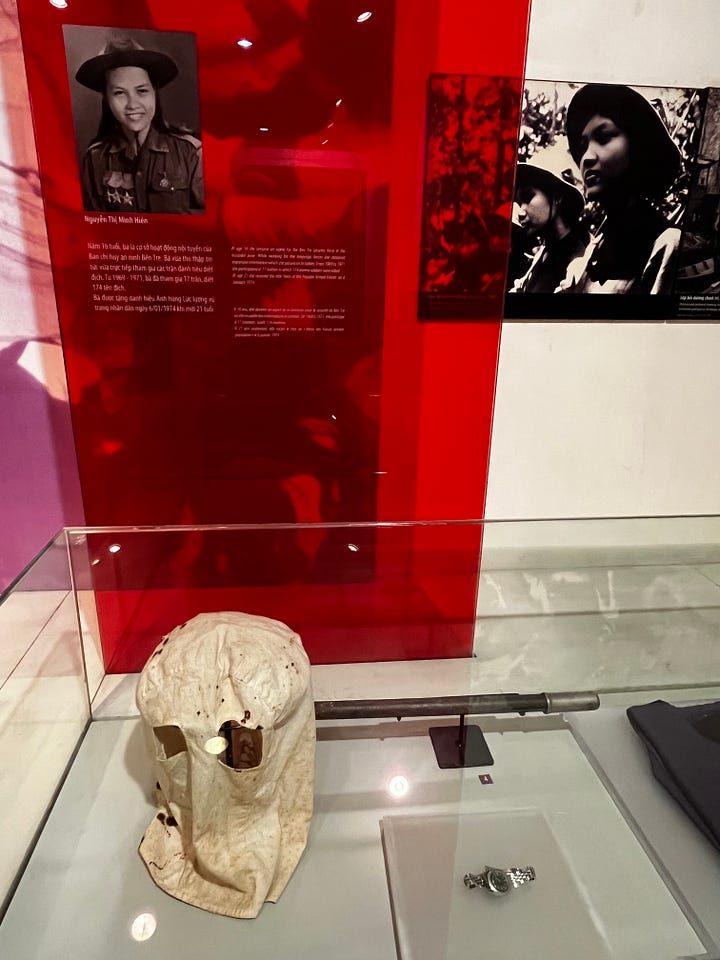

Shown below, this photo of a wounded NVA soldier was given to the nurse who helped him. The mask was worn by one of the South Vietnamese women who met in secret to plan rebellion against the Americans and the southern government. Both women donated these artifacts to the museum after the war.

fashion

The top floor of the museum houses a beautiful exhibit of traditional dress worn by some of the country’s 50+ ethnic minorities as well as a look at fashions in áo dài over the years.

This display shows the wedding costume and bedroom of the Thái Đen (Black Thai) people: