This month I’m making a 12-day drive from Florida through Georgia, Tennessee, Kentucky, West Virginia, Virginia, and the Carolinas. I’ll visit some historic sites with emotional significance for many Americans; Civil War and Revolutionary War museums; state parks; historical associations; and memorabilia and gun shops. To get a better sense of the narratives attached to these places and the events and people they might commemorate, I’ll be looking at the signage, collecting the literature, and talking to visitors, staff, guides, and rangers. And of course, mining the gift shops!

Narrative Nation is my place to collect some thoughts and images as I go. Ideally, some parts of these reflections will be incorporated into the book I am developing with the working title “Loads of Heresy”: White Supremacist Revisions of the American Narrative. But for now these stories are drafts to help me think about what I’m seeing and hearing. Please comment with corrections and add your own experiences with the way our nation’s story—past and present—is being told.

After leaving Atlanta and making the stop at Kennesaw Mountain, we only had about 30 hours in Nashville. We checked into our hotel, took a big nap, and Ubered to the music district. When planning the trip, my husband Ryan and I had no idea we’d be there during the world’s largest country music festival. The sidewalks of Broadway were nearly impassable with short shorts, sparkly boots, big hats, evidence of aggressively plied curling irons, blowdryers, and hairspray, and more than a few people too drunk to see being tugged through the surging maze by a friend with a vice-grip on their arm. The open-sided karaoke party busses passing by on nearly every block and the free cover bands in bar right next to bar right next to bar produced a disorienting aural salmagundi. We found the requisite Nashville Hot Chicken, watched a woman get dumped off a mechanical bull a couple of times because it was possible for us to do that, took pictures of some historic music spots, and walked away from the center so our ride could find us.

That’s one of the stories a visit to Nashville tells about American culture, but it’s not the one we wanted to check out. In the morning, we drove out to Andrew Jackson’s Hermitage. Having read and puzzled over comparisons between Donald Trump and Andrew Jackson, this place was on my list.

The Hermitage

The website and entry sign identify the property as “Andrew Jackson’s Hermitage: Home of the People’s President.” It’s located just outside the city. Turning in to the drive, we glimpsed a thin brown fawn zigzagging leaps behind a doe, nearly hidden by the tall meadow grass. The grounds near the road are not overly manicured and generate that peaceful feeling of a farm at rest.

Born for a Storm

Before our appointed house tour, we watched a 20-minute film about the seventh president. Jackson’s two terms spanned from 1829 to 1837. The film’s title Andrew Jackson: Born for a Storm is something Jackson said in response to the conflicts he encountered and engendered from the beginning of his presidency.

The film gives information about Jackson’s humble origins and some personal details about his wife Rachel that led to scandal at the beginning of Jackson’s political career. She was accused of being a bigamist and attacked by John Quincy Adams in the press. The suggestion is that she died in 1829 as a result of the stress.

Once the “people’s president” topic comes into focus, viewers learn that Jackson was “against political aristocracy” and that his proposed policy of term limits (“rotation”) was controversial. He advocated for a political party system, believing that what was then the Democratic party “were the people themselves” and that “party organization was the only way to ensure that the people remain in power.”

Jackson’s interest in government by “the people” instead of a cadre of political elites did not mean he was too concerned about equality among those people: “distinctions will always exist,” the film quotes from one of Jackson’s documents. Even so, Jackson continued, “the humble members of society . . . have a right to complain of the injustices of their government.” Further, he wrote this: “If the government would shower its favors alike on the high and the low, the rich and the poor, it would be an unqualified blessing.” Jackson is credited with bringing “more people into the process” of American politics than anyone before him.

These grand words and ideals—part of the variously-defined “populist” ethic for which Jackson is known—stand in distinction to his attitudes on slavery. The film does not overtly draw attention to the inconsistency between Jackson’s democratic talk and his enslavement practices, an inconsistency Jackson at any rate shared with many of the nation’s early presidents and big men. Featured historian Annette Gordon-Reed diplomatically notes only that Jackson “never thought anything about slavery as a fundamental moral question.” If Gordon-Reed said more about that, the film doesn’t include it. Instead, Jackson’s success in maintaining the union during a time when the likes of John C. Calhoun were arguing for legal secession of the slave states is the story’s more important thread. Jackson is credited with giving “us an extra thirty years to form bonds” before the Civil War.

Of course that also meant an extra thirty years of enslavement for millions of people, which is a different kind of “bond” than the film intended to evoke, and I was trying to think about that and about who is included in the word “us,” but the lights came on and we had just enough time to truck across the property for the 11 am tour.

House Tour

The property was first called Rural Retreat, and the two-story Greek Revival house that stands today was rebuilt in 1837 after fire destroyed most of the original one. Among Jackson’s losses when the second floor burned were the letters from his deceased wife. The doors and porch columns of the structure he renamed The Hermitage are made from local tulip poplar but fashioned to look like something richer, mahogany and stone.

During the 45-minute tour, visitors hear from several historical interpreters in period garb as they pass from one part of the house to the next. No photography is allowed inside.

Our first guide, a tall, red-headed guy named Finn who reminded me of the young Thomas Jefferson, began with statistics about the enslaved people at The Hermitage. More than a hundred people mostly worked the 1100-acre cotton plantation. Finn held up a laminated photograph that represented Hannah, described as an enslaved woman who was the head of those assigned to the house and who may have been the first person to greet Jackson’s guests. This is a good “front door story” to be told as visitors cross the threshold themselves—every tour has one—but the rest of the script, especially in comparison to some others I’ll write about soon, made it feel a bit like an add-on for the sake of inclusivity.

We didn’t learn much more about the enslaved families. But thankfully, considering the other possible end of the spectrum, we did not hear that “they had slaves, but here they were treated like family.” As my dear friend and public historian Hillary Deitz Delaney tells her own tour groups in Boone County, Kentucky, you can’t say enslaved people were treated like family because you don’t own family. [My story about Hillary and our incredible driving tour is coming soon!]

The tour focused mainly on curiosities and objects of the house and some salacious family history. Overall, I felt we heard too much about Jackson’s controversial marriage, his size 7.5 feet under a lanky 6’1” body, his newspaper collection, and the shortcomings of his ne’er-do-well adopted son referred to as Junior.

I was interested to hear how Jackson’s military background was so important to his sense of his own qualifications for the presidency. Jackson, and the public as well, found a ready comparison to George Washington, the only other president at the time to have come through military ranks. Jackson’s guests were to use “General Jackson” rather than “Mr. President.”

When the rest of our group passed through the back door to see the grounds on their own, we hung back to ask our second guide Brent some off-tour questions. The incomplete presentation of slavery on the property was nagging me, and I had already intended to ask about the numerous comparisons I’ve seen between Andrew Jackson and Donald Trump since the 2016 campaign. The Jackson-Washington comparison seemed to provide a good entry to that conversation.

I asked Brent if he has heard visitors make the Trump comparison. Brent has a master’s degree in history, and from his laugh it was obvious he would have a lot to say about this topic given more time. Though it doesn’t withstand scrutiny, “populism” is usually one connecting thread between Jackson and Trump, and being an “outsider president” is another.

In the film, we learned that Jackson came from more humble beginnings than the presidents before him. Now this can hardly be said of Donald Trump, who inherited his money and his privilege, and thereby his opportunity to become the president. But it’s true that Trump was not a politician, or even qualified to become one, before he was elected.

Besides being outsiders to the political aristocracy, for whatever reason, other commonalities between Jackson and Trump are their crass manners and the tendency to disrespect and threaten. Brent described Jackson as someone who “didn’t give a damn what anybody thought.” He often let his political opponents know this much: “I’ll run it through you if I have to.”

Ryan followed up with Brent to ask what more we know about Jackson's attitudes towards slavery. Obviously Jackson had at least some degree of comfort with the institution’s continued existence. Brent shared information such as Jackson's policies of ensuring that those enslaved at The Hermitage received at least one meal a day (thank you, General?) and of not separating families. Brent was quick to balance any impression of relatively conscionable behavior with the fact that documents show Jackson offering an additional monetary reward for someone to deliver “extra lashings” after catching someone who had escaped from enslavement at his home.

A small sign entitled “A Landscape of Inequality” does good work to correct any impression that Jackson’s family separation policy indicated his personal enlightenment or that the system was ever less than cruel.

Andrew Jackson followed a common “farm management” practice of his time in keeping enslaved families together. Owners thought that this practice, discouraged running away, since it was unlikely that an entire family could safely make their passage to freedom. In addition to encouraging family units, Jackson also chose to cluster housing for the enslaved tightly to confined them to a small easily monitored area.

In spite of finding this sign and hearing a few brief comments on the tour, I left The Hermitage feeling there should be a more palpable incorporation of the enslaved people into the narrative visitors are most likely to hear and retain about that historic property. The Hermitage is owned and operated by a 501c(3) called The Andrew Jackson Foundation, formerly the Ladies’ Hermitage Association, and I hope this organization is compelled to make more changes to their presentation of one of the nation’s most visited historic properties.

Efforts to balance the narrative do seem underway. I’m finishing this story on Juneteenth, and if I were still in Nashville today I could have attended The Hermitage’s line-up of educational events including presentations on how the foodways of enslaved people at The Hermitage have influenced American cuisine; the trades and arts of African Americans during and after their enslavement; and the cabin of a man named Albert who lived there longer than anyone else and remained after gaining his freedom. On The Hermitage website, a “Slavery” tab includes more history of the families enslaved there, even acknowledging that Hannah—the woman we heard about at the front door—escaped with one of her daughters to Nashville during the Civil War “[d]espite the seemingly close relationship” she had with the Jacksons.

Instead of tucking Hannah’s escape from enslavement into the website, that humanizing information could be emphasized in the house tour when her picture is shown, replacing some of the more tiresome details about candlesticks and Jackson’s adopted son who was an alcoholic and couldn’t manage the accounts. Similarly, the tensions in Jackson's attitude toward enslavement could have made their way into the public-facing story most people would hear in the main tour.

I discovered more information after the fact. While writing this story and going through the website, I found an additional $15 thirty-minute wagon tour called "The Hermitage Enslaved." It looks like a pretty light drive-through experience. For $55 more (on top of $27 for the house tour), there is a slavery-focused walking tour that, I assume, can go deeper. Neither slavery tour is available on weekends (when we were there), so this information did not come up when I bought tickets for our date online. No one speaking to us (about five people during our visit) mentioned that more detailed information is available.

While I give The Andrew Jackson Foundation credit for these options, my central response to their presentation is still the same. In the flow of a standard visit, you watch the movie as you enter the visitor's center and then go to the house tour, neither of which engages the question well. Visitors have to arrive at select times and personally choose to get information about enslavement. The wagon tour cannot be purchased in advance. I would hope to see all these pieces—the story of the Jacksons and a fuller story of the African Americans who at all times constituted at least 95% of the people living there—incorporated into one fluid tour. Visitors should leave this property with a greater understanding that stories of white people in America cannot be accurately told while stories of black people are contained between parentheses (revealed at certain times for an additional cost).

These posts are not intended to be Yelp! views of historic sites and tours. I’m trying to gather my thoughts on the ways stories are often told so incompletely, and how narratives received by the public may hold the door open for today's growing white nationalist and white supremacist movement. Every diminishment and omission of the African-American experience in favor of the white experience makes it easier for white supremacists to convince themselves and others that this nation is a white nation and that non-whites are never the real story and should not occupy too much space in our national narratives.

Nashville’s Bicentennial Capitol Mall

We still had time for an afternoon in Nashville before I dropped Ryan at the airport to continue my trip alone. After driving downtown to get a look at the city without all the CMA festival goers, we saw some brown signs and parked next to the state archives building to walk around the cumbersomely-named Bicentennial Capitol Mall State Park.

Like a miniature version of the National Mall in Washington, D.C., the long grass field of the Bicentennial Mall is intersected by sidewalks and framed by important cultural buildings. The sense of being on a trip through American history was bolstered by a vintage baseball game.

After crossing the park and nearly getting bonked on the head by a flying baseball, we stood for a while reading from the Pathway of History, a 1400-foot long series of granite markers containing a fairly inclusive timeline of Tennessee state history. Progress and achievements for women, African Americans, and labor rights are well represented alongside technological milestones, political events, and a history of the state’s education system.

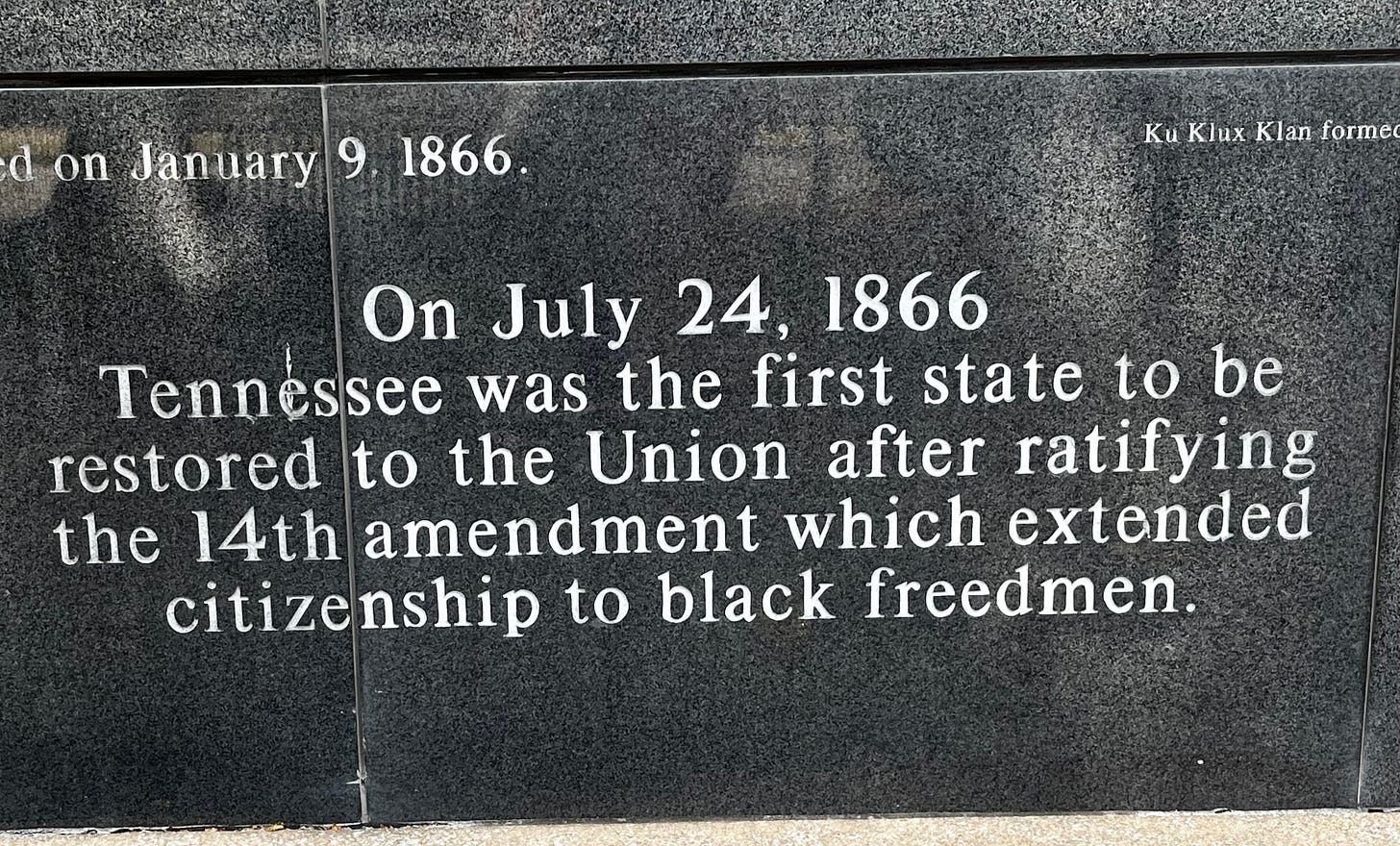

Several sections of the path are partially broken to represent Tennessee’s deep divides about the Confederacy. A section about Tennessee’s restoration to the Union also includes a much smaller notation about the founding of the KKK, which we know happened in response to the end of slavery. Farther down the wall, the disbanding of the original KKK (but stay tuned, because they’re never really gone) is noted beneath an explanation of the new 1870 State Constitution that affirmed the abolishment of slavery and the voting rights of African American men.

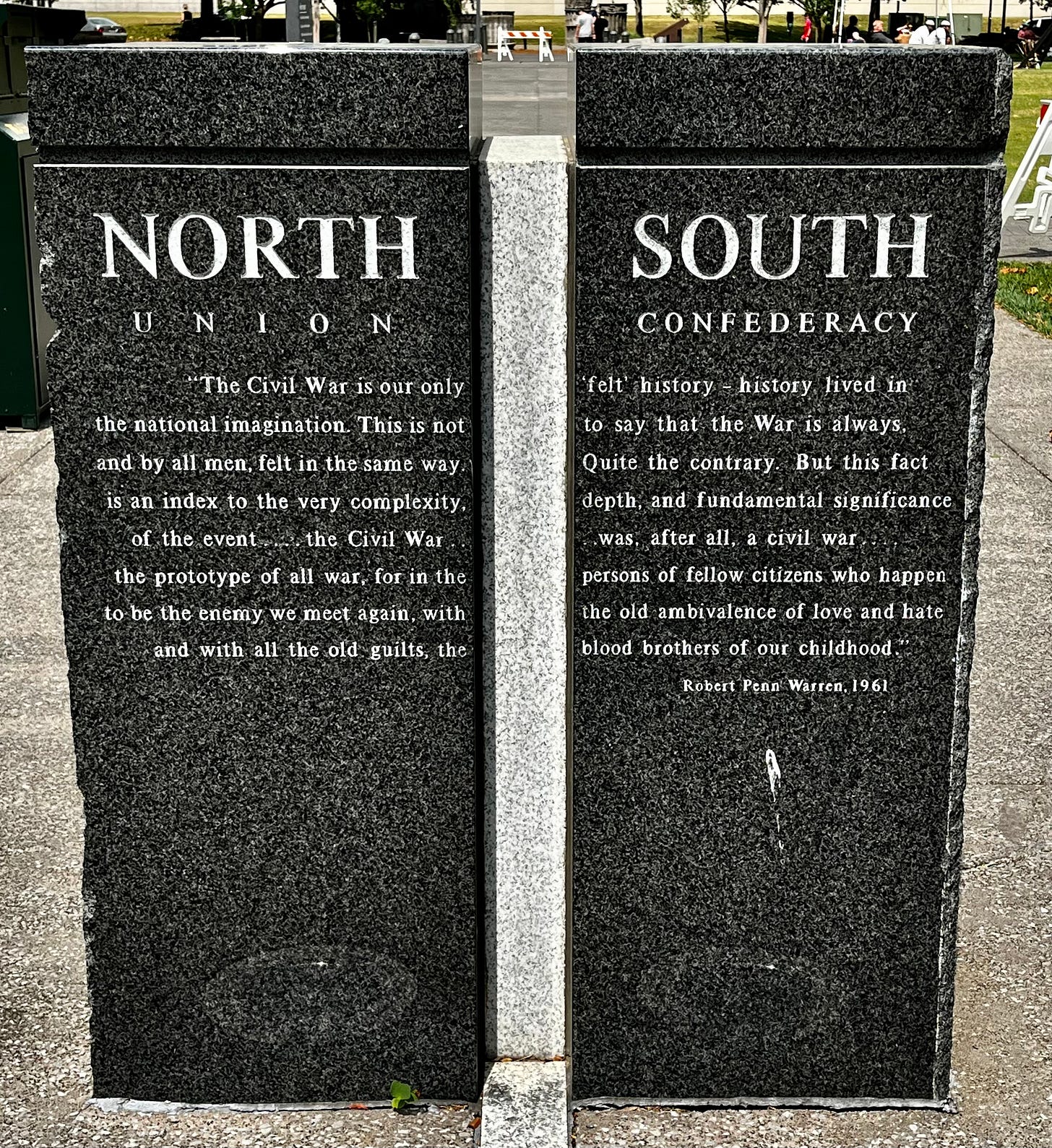

By dramatizing the divide between Confederate sympathizers and Union loyalists as well as the fact that Tennessee was the last state to join the Confederacy and the first readmitted to the nation after the war, Nashville’s Pathway of History leans away from any kind of Lost Cause devilry or even sentimentality.

Standing separate from the timeline, a passage from American writer Robert Penn Warren’s 1960 book The Legacy of the Civil War reminds us how a civil war in particular is destined to continue: it is “history lived in the national imagination” again and again.

And it is just this capacity for emotional reanimation of our civil war, I fear, that gives today’s white nationalists, with their calls for a new civil war and a “national divorce,” too much influence over the public narrative. They really need to be shut down.

Too serious? Racial and political strife are not the only stories we heard about in Tennessee, which also played an important part in the history of American deliciousness!

I may need a bit to unpack everything in here! I thank you for the links, that will help. It seems like the Hermitage is still at the baseline of inclusion in their historical narrative, taking "baby steps" toward a realistic presentation. This is true of most tourism-driven historic sites of enslavment. I noticed they offer event rentals, the website has as slick "wedding" video that I watched (sound off.) There was a very light sprinkling of non-white people in the mix; again, doing the very minimum.

Celebrations at enslavement sites are tricky, particularly for history lovers. The income generated by these expensive rentals does a great deal to support preservation, so there's that part, but paying a lot of money to kick off your married life on the grounds where people were held in bondage for traumatized generations is weird, even for the most tone-deaf among us. Keep it coming, I'm enjoying your journey!

While I understand your concern about sounding too much like a consumer review, the depth of analysis you bring to your observations are very much appreciated and elevate your commentary leaps and bounds ahead of what any Yelp review might deliver. I especially appreciate how you connect your critique of the tour's standard presentation to logically extrapolate what effect it may be having on further emboldening the dreadful conspicuousness of the white supremacist movement. This is important work. Thank you.