This month I’m making a 12-day drive from Florida through Georgia, Tennessee, Kentucky, West Virginia, Virginia, and the Carolinas. I’ll visit some historic sites with emotional significance for many Americans; Civil War and Revolutionary War museums; state parks; historical associations; and memorabilia and gun shops. To get a better sense of the narratives attached to these places and the events and people they might commemorate, I’ll be looking at the signage, collecting the literature, and talking to visitors, staff, guides, and rangers. And of course, mining the gift shops!

Narrative Nation is my place to collect some thoughts and images as I go. Ideally, some parts of these reflections will be incorporated into the book I am developing with the working title “Loads of Heresy”: White Supremacist Revisions of the American Narrative. But for now these stories are drafts to help me think about what I’m seeing and hearing. Please comment with corrections and add your own experiences with the way our nation’s story—past and present—is being told.

Old Johnny Reb

My short visit to Glasgow included an early run that took me past a 1905 statue of a generic Confederate soldier. The monument’s three simple inscriptions are C.S.A., Our Confederate Dead, and the dates of the war.

Continuing through the city center, I thought about the origins and the impact of that C.S.A. reference. Glasgow—with its hip murals, smoke shop, international restaurants, and manicured public spaces—did not appear to be some disconnected or dying little town. Not far from Nashville and Louisville, this city has surely felt the recent wave of Confederate monument removals and contextualizations. It’s hard to believe there’s any kind of contemporary local consensus that the Confederate States of America should have survived.

Kentucky’s status in the Civil War is a bit complicated, at least for someone who has never learned about it. At first the state held a position of “armed neutrality,” followed by three short months as a part of the Confederacy (October 1861-January 1862) before being restored to the Union. About 100,000 Kentuckians fought the war on both sides, but Union troops outnumbered Confederates roughly three to one. African Americans born free or escaped from slavery accounted for about 20,000 of those Union fighters.

In 1862, Glasgow was raided twice by the Confederates, once under Morgan and later under Bragg. Learning this made me even more curious about why a monument to the C.S.A. survives outside the courthouse. But apparently a high number of Barren County men received a commendation from C.S.A. President Jefferson Davis, and it was based on this legacy that J.A. Murray was able to partner with the Kentucky Women’s Monumental Association to raise the money and the support for the statue.

The origins of the monument—locally known as “Johnny Reb”—would come up during breakfast that morning and again while visiting the Museum of the Barrens.

Museum of the Barrens

The South Central Kentucky Cultural Center, or the Museum of the Barrens, is located on Water Street in Glasgow’s old pants factory. A sign in the museum explains its general purpose, to highlight the ways “local history of the Barrens intersects with global and national history.”

That mission is certainly accomplished, and in some pretty interesting ways. I stayed there for about 90 minutes, stunned by the number and variety of important or famous national and global events connected to members of this small community.

Luck brought me to the museum’s new director just as soon as I entered the building. Debbie Pace was sitting at the front desk taking care of some paperwork. After explaining my interest in how the American story is being told, particularly related to race relations, immigration, white “settlement,” and the Civil War, I asked if the museum has recently changed any of its signage or exhibits, has plans, or has been pressured to do so.

Debbie said that she was well aware when she took the job a few months ago that there could be several signs or narratives needing significant updating or even removal. She suggested I get started on the first floor, and she would join me after a while. There were a couple of items she wondered if I’d have any comments about—if I didn’t spy them on my own, she’d point them out.

Almost everything on display in the jam-packed three-story building was donated or loaned by community members. Debbie said it would be very unusual for the center to seek or cultivate materials. This is an interesting difference from other museum collections driven by some curatorial plan or influenced by the vision of a board—here, the museum’s narrative is driven by what the community is willing to bring out. From there, these local family artifacts are arranged into a timeline as well as into themed exhibits such as a general store, a 1950s kitchen, or the nearby caves.

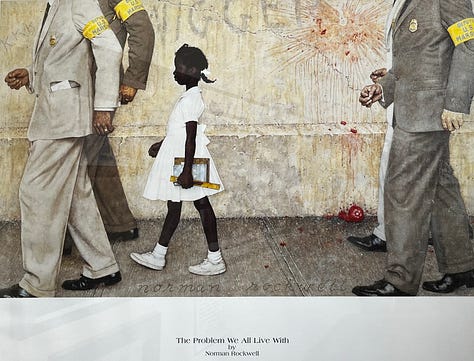

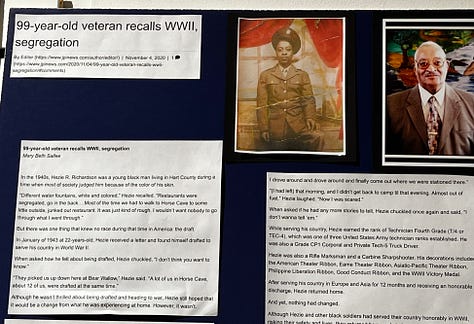

I saw a lot of fascinating artifacts donated by Barren County’s African American families. Norman Rockwell’s Ruby Bridges painting is included because one of the marshals assigned to escort her came from Barren County. Other items document African American military history, including a published interview about a World War II veteran’s return to the still-segregated South. Another clipping tells about businessman Stephen Landrum who, though illiterate himself, donated a building for the first black children’s school in the area.

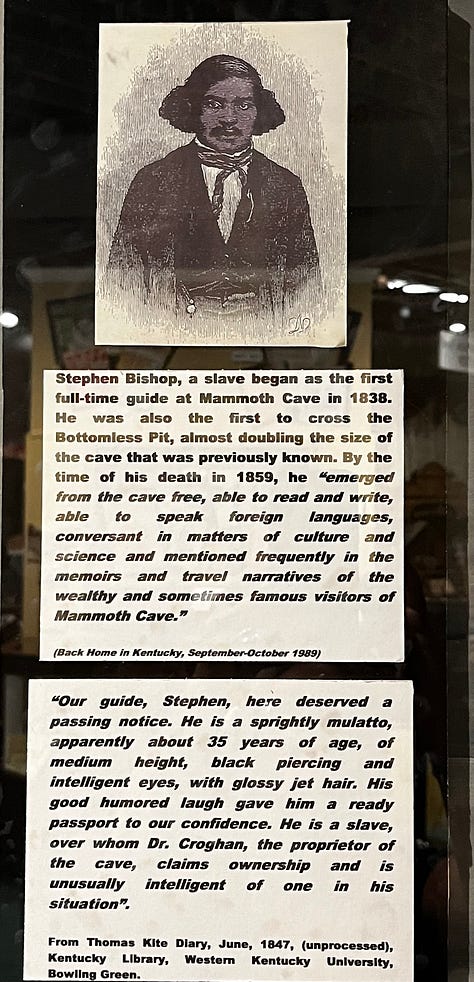

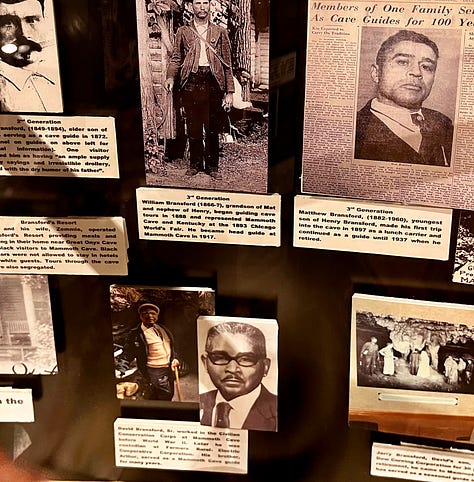

The story I found most engaging was that of Stephen Bishop. An enslaved man, Bishop worked as a guide inside Mammoth Cave for over twenty years, during which time he became educated and also something of a celebrity among wealthy tourists who mentioned him in their travel journals. He was freed in 1859. Another display shares the Bransford family’s 100 years of guide work in Mammoth.

While the museum includes a lot of significant exhibits featuring people of color, it also houses one item that contradicts the respect being shown for those legacies of success.

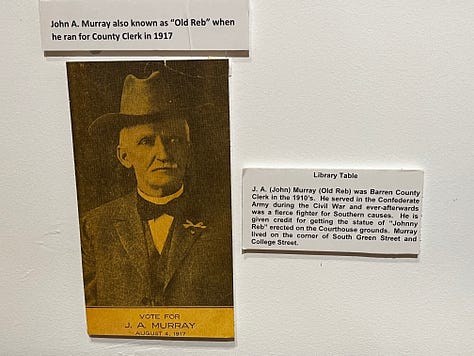

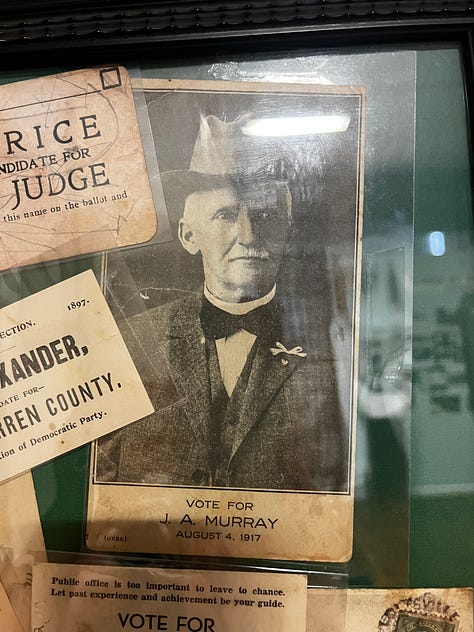

Shortly after Debbie started her position at the museum, a long-time volunteer suggested they take down a picture of one local man: the J.A. Murray affiliated with the Confederate statue. The current wall sign reads,

J. A. (John) Murray (Old Reb) was Barren County Clerk in the 1910’s. He served in the Confederate army during the Civil War, and ever-afterwards was a fierce fighter for Southern causes. He is given credit for getting the statue of Johnny Reb erected on the Courthouse grounds. Murray lived on the corner of South Green Street and College Street.

Debbie immediately saw why the Murray picture—oddly placed in the World War II section—was a candidate for removal.

Talking to people who had been with the museum longer, Debbie discovered that Murray’s family had donated the old library table over which his picture was posted. His table, though in poor repair, is perennially in use as a display stand by the museum, so the J.A. Murray corner remains—much more a passive than an active commemoration of the town’s most visible old rebel.

The circumstances of this small sign bring me back to the type of museum this is and why there might be more room for a person like Murray there. Does the fact that he was something of a local character make a space for him in a community-driven collection, regardless of his politics? I don’t have the answer to that, but he’s definitely as much a part of the local history as other people I saw represented at the museum. His connection to the war and later to the statue fit the mission.

If Murray’s photo and library table must remain, at the very least a new sign is needed. Perhaps this could be done in conjunction with more information about the ways a minority of Kentuckians got behind the Confederacy during the war and the Lost Cause decades later when Johnny Reb was erected. For that to happen at this museum, the public will need to provide the materials to tell the story more completely.

Fascinating and enjoyable story! This is a prime example of how a community’s contributions shape public historical narratives, and thus “history” itself!

I see the history is lost on you. I am from Barren County. Barren County provided around 1200-1500 confederate troops. The only union-leaning area was Etoile. Near the Metcalfe County border. Men from this county nearly made up the entire 6th Kentucky Infantry. Not to mention, general Joseph H Lewis, who commanded the 6th KY, was from Barren County. And is buried in the Glasgow cemetery. When he died it was the biggest parade in Glasgow. His body was packed to the grave followed by a massive crowd. Confederate flags were hung out of buildings. His former soldiers from Barren County were his pallbearers.

Barren Countians also filled 2 companies with the 4th Kentucky Infantry. Led by Barren County native Col. Joseph Nuckols. And 1/3rd of Morgan’s 2ndKY cavalry came from Barren County. Morgan never “raided” Glasgow. There was a union garrison here from Michigan. Morgan came here to let his men stay at home for a while for Christmas. They skirmished with a union garrison until they ran off to cave city. Leaving Morgan’s men to assimilate with friends and family.

John Murray put the monument up to remember the men he served with from Barren County. And as a way to grieve.

He would frequently tell children “that could be your pappy up there”. Oh, and by the way. When it was unveiled a massive crowd was also there to see it and celebrate. It became a tradition to place a reef on Johnny Reb every christmas.

Barren county was devastated by the war. Many young men never came home. The statue was a way to grieve and reconcile. Not celebrate slavery, or white superiority.

To act like the monument was put up because a “minority” of people like John A Murray and other like-minded individuals. Wanted others to feel their “bigoted world view” Is just false. Barren County was confederate leaning area.