Thanks for visiting Narrative Nation!

This is where I’ll collect some thoughts and images from my exploration of places with emotional significance for many Americans. Stops include Civil War and Revolutionary War sites and museums; Underground Railroad sites; state parks and historic homes; historical associations; and memorabilia and gun shops. To get a better sense of the narratives attached to historic places and the events and people they might commemorate, I look at the signage, collect the literature, and talk to visitors, staff, guides, and rangers. And of course, I mine the gift shops! Other places such as a Christian theme park, a convenience store, and a gun show help me consider how ideas about history influence current American fascinations.

Some of this will be incorporated into the book I’m developing with the working title “Loads of Heresy”: Far Right Revisions of the American Narrative. For now these stories are drafts to help me think about what I’m seeing and hearing.

This is my second post about the presentation of enslavement, Underground Railroad history, and African American lives after emancipation in Boone County, Northern Kentucky. If you missed the first one and want to read more about why this area is so important to the history not only of enslavement, but the resistance to and dismantling of that institution, you can find it here.

Another thread in my driving tour with Boone County Public Library’s Lead Researcher on African American Initiatives, Hillary Deitz Delaney, was the story of Margaret Garner. We stopped at several locations connected to this famous woman’s life in Kentucky. Thanks to Hillary for answering all of my follow-up questions.

Garner’s story is well documented, but it’s worth a few paragraphs of review here before looking at the ways that story is publicly shared in the places it happened. Some of the minor details are hard to settle among the varying accounts.

Margaret “Peggy” Garner (1834—1858) was born enslaved in Boone County. Her father is believed to be the white man John P. Gaines who owned Maplewood Plantation in Richwood. When Margaret was about fifteen years old, John became the governor of the Oregon Territory and sold the property to his brother Archibald. Margaret was included in that property.

Archibald Gaines is understood to have forced sex on Margaret for years. Though still a teenager, Margaret was married to a man named Robert Garner who, along with his parents, was enslaved by the neighboring Marshall family. She was already pregnant with Robert’s child when Archibald Gaines assumed ownership of Maplewood. But her next three children (Samuel, Mary and ‘Scilla) were near white, and Archibald was the only white male living on that property. The timing of each birth suggests that Margaret was impregnated during what would have been his white wife’s periods of restriction during her own series of pregnancies. Rape of enslaved women, married or not, by white men, married or not, was a common (and legally permissible) occurrence throughout the slavery era in every state.

In 1856, when her fourth child was less than a year old and she was pregnant with the fifth, Margaret and her family, including Robert Garner’s parents, escaped by traveling about sixteen miles to the community of Covington and walking across the frozen river to the free state of Ohio.

They reached the Cincinnati home of Elijah Kite, a formerly enslaved man described in some accounts as a family friend. Kite was working with Quaker abolitionist and Underground Railroad activist Levi Coffin, but the Garners were discovered before the next stage of their escape could be executed. As her husband tried to fight off a group of men that included Archibald Gaines, Margaret cut the throat of her daughter Mary to spare her a lifetime of enslavement and rape. Contemporary reports say Margaret attempted to kill the other children also, but everyone else was captured alive.

Margaret was held at the Covington jail during a trial that lasted about two weeks and attracted large crowds. Margaret’s lawyer argued she should be charged with the crime of murder, not the more common charge of escaping slavery and stealing property (in this case her own children). Such a charge in the state of Ohio would have been a means to keep her in a free state instead of being returned to slavery according to the federal Fugitive Slave Act passed about five years earlier. This attempt and another one based on religious conscience were rejected by the judge, and the Garners were returned to Kentucky. When an extradition order was finally granted to bring them back to Ohio for a murder trial, Archibald Gaines managed to move them around Kentucky and eventually sent them down the river to relations at Gaines Landing, Arkansas. The abolitionist newspaper The Liberator summarized the tragic story and described the riverboat wreck that resulted in the death of Margaret’s baby (the story is on page 47).

Once in Arkansas, the rest of the family was quickly sold for plantation labor in Mississippi. Margaret died at the age of 25 during the typhoid epidemic of 1858. Her husband Robert survived to fight in the Civil War and eventually returned to live in Cincinnati until his death in 1871.

Now for a look at how this important story is currently shared with the public.

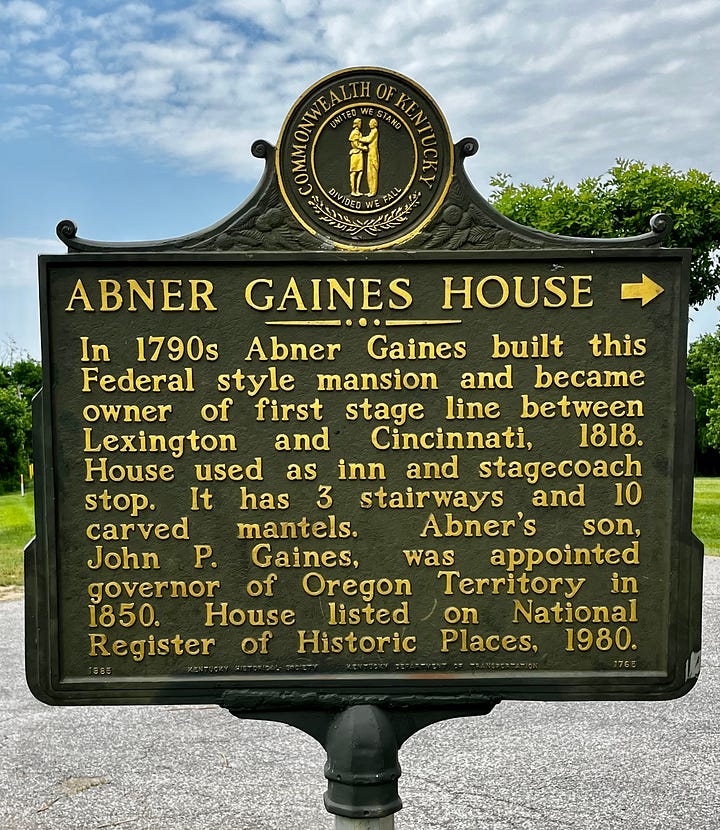

The first set of images below features Gaines Tavern, a house built in 1790 that later became an inn and stagecoach stop. It’s the oldest house in the City of Walton. The owner Abner Gaines is noteworthy because, as the Kentucky Historical Society’s historic marker explains, he was also the “owner of [the] first stage line between Lexington and Cincinnati.” The marker also mentions Abner’s famous son John Pollard Gaines, who became the governor of the Oregon Territory in 1850.

The marker does not include information about the Garners or any other African Americans. Margaret Garner’s mother Priscilla was enslaved there and probably born there, and Margaret would have spent some of her childhood there before being moved to John P. Gaines’ property a few miles away. The Abner Gaines house was listed on the National Register in 1980, and the marker is dated 1985.

The next set of images relate to two important sites in Margaret Garner’s life: the Richwood, Kentucky property called Maplewood, which was owned by Garner’s white father John P. Gaines and later her rapist Archibald Gaines; and Richwood Presbyterian Church, where Margaret was a member of the congregation.

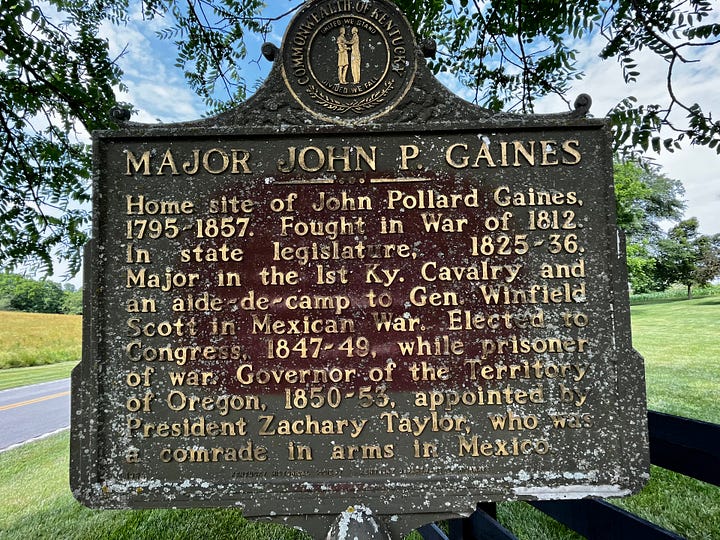

Again, neither the marker at Maplewood (the location where she was enslaved and from which she escaped) or at Richwood Presbyterian Church mentions Garner. Each one concentrates only on the illustrious deeds and personal connections of white people. The marker for the “home site” of Major John P. Gaines (1795-1857) lists his military and legislative experience as well as his connection to President Zachary Taylor, but not that he was the father of Margaret Garner or that this was her “home site” too. The marker for the church mentions the founder’s connections to President William Harrison as well as his wife’s important Presbyterian lineage.

At a third location, the signs of Margaret Garner are found!

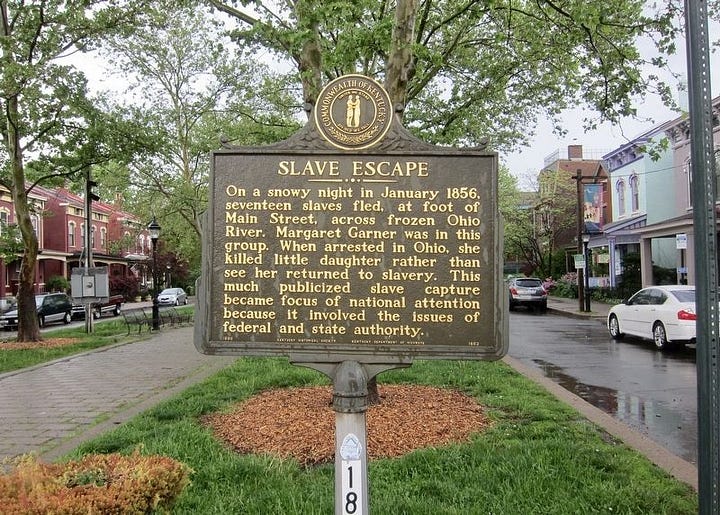

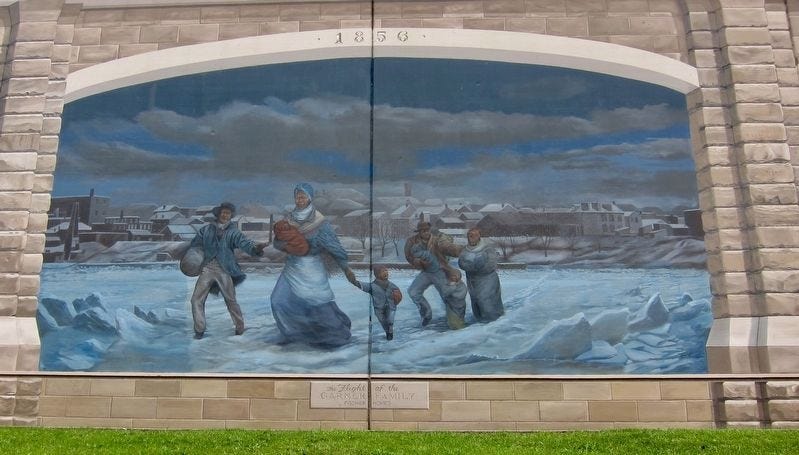

In Covington, Kentucky, where the Garners and the rest of their party crossed the Ohio River, a historical marker is labeled “Slave Escape” on one side and “Controversial Judgment” on the other. A nearby mural at the floodwall, painted in 2003, depicts the family’s escape.

The timing of these public history utterances seems to matter. While the historical markers posted in 1985 fail to recognize Garner in places important to her life, the marker placed in 1990 describes her family’s struggle for freedom as well as the controversial public aftermath and the impact on the abolitionist cause. Between those years, Morrison’s 1987 book was released.

With time for more research on the reconstruction of this history for the public, I’d want to contact members of the Kentucky Historical Society and whatever other committees were involved in planning these markers to find out whether Morrison’s literary tribute to Garner influenced their awareness of the case or their sense of its public importance.

Perhaps the Kentucky Historical Society was unaware of Garner before Toni Morrison’s novel made her—or at least a fiction inspired by her story— internationally famous. But Beloved was published more than 35 years ago, and three of the four markers examined here still do not speak the name of Margaret Garner or any other African American.

The “Slave Escape” side of the Covington marker explains how the debate fit into a larger conversation about slavery: “This much publicized slave capture became [the] focus of national attention because it involved the issues of federal and state authority.” As I read more about the Garner trial this week, I was struck by the irony of the jurisdiction debate. The Fugitive Slave Act was a federal law requiring the return of captured people to their enslavers, even when that action contradicted state law. Only a few years after a judge determined that federal law would take precedence over state law in order to keep the Garners enslaved, the southern states seceded from the Union rather than submit to federal law—again, in order to keep people enslaved. But unsurprisingly, the specious "states rights" argument on which the Confederacy hung its hat did not fly when it would have benefitted one Black family in 1856.

Margaret Garner’s family story matters for so many reasons. Aside from the moral complexity and power of Margaret’s choice, and the way her trial illuminated the tension between state and federal law, her family’s story can also help us understand more about the nation’s first civil rights movement, the Underground Railroad. As we dedicate more monuments to people of color and recognize more African American history, surely this is an essential case.

Surely it’s time to stop compounding the historical suffering of the Garner family by ignoring their history in some of the most obvious narrative sites. In part one of the Boone County story, I also noted that the historic marker in front of the Dinsmore Homestead is the least inclusive element of the site.

In an email to Hillary, I asked for her concerns about the state of public history in Kentucky.

As a researcher who has spent a great deal of effort balancing the public narrative in Boone County, I'm concerned about the grass-roots effort to remove any discussions of race, enslavement, Civil Rights, etc. from being taught in our schools, along with discussions of LGBTQ+ issues nationwide. Though the Kentucky legislature has passed legislation along these lines in terms of how history is taught in KY schools, this does not mention library programming; but we are aware of this growing national trend.

That being said, our Underground Railroad in Boone County Bus Tour has been our most popular public offering since its debut in 2013. We will continue to discover and share the previously undocumented people and events in our county history.

Her response illuminates the difference between what the real majority of people care about and the purported priorities of the fictionalized majority portrayed by right-wing disinformation campaigns.

The work of historical societies and commissions has generally been completed by people who skew older, richer, and white. The historic markers carry weight—probably more weight than they should because they are often put together by small groups of self-selected, well-connected locals who may not be the best suited to assess the current narrative and improve it. I don’t think these committees mean to support the work of right-wing legislators and their supposedly grassroots constituent-activists (who, as in the case of Moms for Liberty, are often well-funded and well-connected operatives for anti-democratic interests). Now that all this recent legislation allows us to see so clearly the right wing agenda of making Black history invisible, local historical commissions and researchers have the opportunity to use historical markers to keep that history above ground.

Just like the Underground Railroad, the Boone County Public Library’s bus tour is not invisible, but it’s not the state’s official narrative either. The tour reconstructs some parts of that history, but unless those street-level official historical markers catch up, we still have the official story and the underground story; the story you see right away any time of the day, and the story only a few people are involved in telling and that you have to go out of your way to discover.

Here’s a story within the story that helps us see the possibilities for improving public signage and education about Black history—and in the process, yes, “uncomfortable” truths about white history—through a combination of legislation, funding, public historians, and volunteers. It’s happening right now in my home state.

This week I learned about Virginia’s new HB 1968, a bill that provides historic markers at surviving locations named inThe Negro Travelers’ Green Book. The Green Book was started by Victor Hugo Green, a New York City mail carrier who wanted to publicize safe places for Black travelers to dine, get gas and other services, or stay the night. It was published from 1938-1967. The image below shows a few of the editions, courtesy of a public history project called The Architecture of the Negro Traveler’s Green Book.

The project’s website explains how another initiative to share Black history with the public in a free and accessible format catalyzed their own:

It all began with the New York Public Library's announcement in 2016 that it had digitized all of The Green Book guides in its collection.

In the summer of 2016, Anne Bruder, Susan Hellman, and Catherine Zipf formed a research group that sought to find out what had happened to the Green Book’s buildings in their states (MD, VA, and RI respectively). After a presentation at a Southeastern Society of Architectural Historians conference, the three were inundated by a host of other scholars wanting to learn more about sites in their states. With the help of these scholars, the project has evolved into an effort to document the history and status of every building listed in The Negro Traveler’s Green Book. (“About”)

Researchers from around the country are now collaborating to identify and contextualize surviving buildings and, in the State of Virginia, submit applications for the state-approved markers. In Virginia, a new historic marker costs about $3,000.

Shifting back to the story of Margaret Garner in Kentucky, something like $3,000 per sign seems within reach and well worth the effort to provide more well-positioned public information about Black resistance to slavery—and the system’s cruel response to that resistance—in the years after the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. Putting the signs right at the white-owned properties is important. The connection to Morrison’s important novel only increases the likelihood that members of the public encountering Garner’s story on a historic marker would seek more information and participate in sharing true American history.

I think it comes down to a question of who owns the public-facing story of what happened in these places. Public markers written in the good ol’ style suggest that the answer is still too often the white land owners, house owners, and business owners and not the Black people who were themselves legally owned and forced to live and labor in those places.

You're doing so many different things here. You're marking sites and marking the not-official-marking of sites. It's astounding, in fact, that so much of an historical trail exists to illuminate Garner's story through the landscape. Virginia's new bill re Green Book sites is promising -- especially with/despite Youngkin as governor. I love the notion of reading text through the landscape, a necessary three-dimensionalization of history.