Thanks for visiting Narrative Nation!

Email recipients: please click to read this longer story in the Substack app instead!

Some of this will be incorporated into the book I’m developing with the working title “Loads of Heresy”: Far Right Revisions of the American Narrative. Though I write about some current political events related to my subject here, this is mainly where I collect thoughts, images, and a bit of research from my own exploration of places with emotional significance for many Americans. So far, stops include Civil War and Revolutionary War sites and museums; Underground Railroad sites; state parks, schools, historic homes, and historical associations; and memorabilia and gun shops. To get a better sense of the narratives attached to historic places and the events and people they commemorate, I look at the signage, collect the literature, and talk to visitors, staff, guides, and rangers. And of course, I mine the gift shops! Special stops such as a Christian theme park, a convenience store, and a gun show help me consider how ideas about history influence current American fascinations, conspiracy theories, and cultural conflicts.

Narrative Nation is free to read, though paid subscribers are deeply appreciated and enable me to spend more time writing. Re-stacks also help me grow my readership. Thank you for being here!

Every city tells its story in its own way, but local media is always one of the most influential vehicles for that narrative, and a community’s past and present priorities can be read in its monuments and place names. To capture some of the ways Richmond has done it, here I meander across two newspaper editors, two monuments, and three or four schools. I’ll pick up my Retelling Richmond series from the hotel window at E. Franklin and 5th Streets in the Riverfront district.

I looked out at some important words on the side of a beautifully restored building: Richmond Free Press. The city’s current Black-owned newspaper was founded in 1992 by former Howard University professor Raymond Boone. In today’s news market, it’s encouraging to see this independent publication’s circulation continuing to grow. The paper’s website notes that it has “successfully championed causes that promote equality with justice and opportunity for all people” and that its founding “changed the media landscape of Richmond, the former Capital of the Confederacy.”

“the fighting editor”

The story of Black-owned, justice-minded newspapers in Richmond goes back 147 unbroken years, as far as I know. TheVirginia Star ran from 1877 to 1882, printed from its offices on Broad Street. (I’m putting a pin in the story of the Star until I can find out more about it.) In 1882, thirteen formerly enslaved men founded the Richmond Planet under the leadership of Yale Law School’s first African American graduate, Edmund Archer Randolph. Two years later, 21-year-old John L. Mitchell, Jr. (1863-1929)—a man who was born into slavery at Laburnum near Richmond during the Civil War—began his 45-year tenure as editor of the Planet after the city’s new school board removed Black teachers from the Richmond Colored Normal School.

The Planet was published on Saturdays, first from Mitchell’s place at 222 E. Broad in the Jackson Ward neighborhood, and moving a few blocks down in 1888 to Shockoe Hill to have more space in the basement of Swan Tavern. The paper’s masthead included two slogans in the mid-1890s: the admonition that “EVERY COLORED MAN Should Have This Journal in His Home” and the reminder that this was “The ONLY MEDIUM for Advertisers Desiring Colored People’s Trade.”

A cartoon on the February 23, 1895 front page was titled “White Men to the Rescue.” This was Mitchell’s response to a letter from a “wealthy white Democrat” who assured him that he “discountenanced the acts of oppression” African Americans continued to face in the Jim Crow South. As another lynching is underway, a group of “liberal-minded whites” approach under the apparently ineffective banner of “law and order.” A half-column to the right noted the unexpected death three days earlier of “Fred’k Douglass,” “the great colored orator” and “unquestionably the best known colored man in the world.”

This pairing on the page—the passing of Douglass and the sardonic lynching cartoon—provides a reminder of how far we were from anything like Black safety and equality in Richmond, despite the work of Douglass and despite the proffered support of some “liberal-minded whites.” Mitchell consistently used the paper to draw attention to the struggles, the successes, and the civic life of Black Americans. His aggressive anti-lynching journalism and arguments against Jim Crow earned him the nickname “the fighting editor.” While liberal whites may have been content to "discountenance” the racial violence, Mitchell was encouraging Black men to arm themselves in public. In 1904, he used the paper to drive a year-long boycott of Richmond’s segregated electric streetcars. But the campaign eventually ended without success when even more restrictive state-level segregation legislation passed.

Mitchell served as editor until his death in 1929, and the Planet continued independently for another decade until 1938 when it was purchased by the Afro-American (a chain of Black-owned newspapers that started in Baltimore in 1892, also founded by a formerly enslaved man). Under a series of similar names, the Richmond Afro-American was published until 1996; the Library of Virginia’s exhibit “Born in the Wake of Freedom” claims it was the longest continuously running Black weekly in the country.

The stories of these early Richmond papers created for and by the African American community are documented briefly online and deserve more public attention than they have received. Recently, as the Confederate monuments that cast such a shadow have left the city, more light has been cast on the history of Black Richmond—I think this double adjustment of the narrative is the case in many places. In 2022, a 26-minute documentary, Birth of a Planet: Richmond on Paper, was created by several Richmond businessmen who interviewed descendants of Mitchell and one of the Planet’s founders. I’ll come back around to Mitchell in a minute.

“saaa-luuute!”

The last 25 years of the Richmond Planet overlapped with the career of another influential Richmond newspaperman named Douglas Southall Freeman (1886-1953). Freeman—whose father Walker Freeman fought for the Confederacy and was there when Lee surrendered at Appomatox—embodied Old Virginia white supremacy in 20th-century Richmond.

He used his platform as editor of the Richmond News Leader from 1915 to 1949 to defend both segregation and eugenics. With the same commitment that John L. Mitchell had written against the scourge of segregation from his public platform, Freeman had written against its cure. A 2021 report on Freeman’s civic influence created by the University of Richmond notes that

his stances on race and racial issues profoundly affected opinion, practice, and policy during his lifetime and helped to lay the groundwork for Virginia’s organized resistance to integration.

Freeman is still heralded by Confederate apologists who describe his 1935 four-volume biography of Robert E. Lee as a portrait in Christian values and American character. But credible historians understand that these books, and Freeman’s approach to the Civil War period generally, did a lot of damage to the public’s understanding of history by bolstering and authorizing the Lost Cause. Freeman is associated with the “Virginia School” of Civil War history:

Freeman’s books showed a preference for campaigns over social and political history and a sympathy for his Confederate subjects that was greater than that of many later historians. In particular, his failure to grapple with the role of slavery in the war and his elevation of Lee to near-mythological status have been criticized as helping to fuel the mythology of the Lost Cause. (Encyclopedia Virginia)

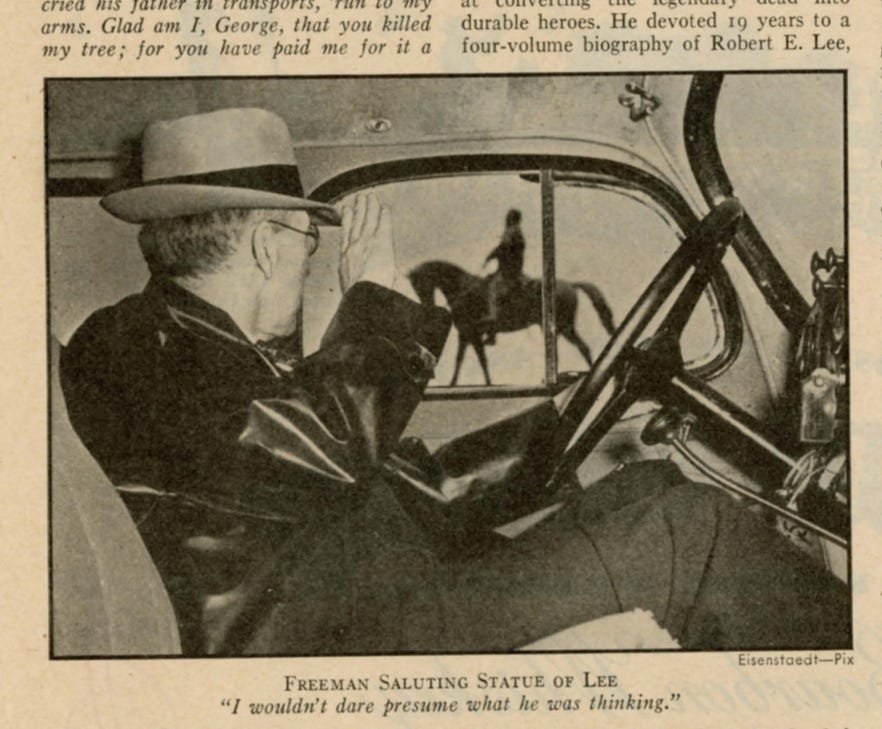

The way some Southerners revere Freeman is mirrored in the well-known story of the man’s own tireless attraction to Robert E. Lee, a personal interest that spilled beyond the books. As he drove through the Fan to his office at the News Leader, Freeman saluted the Lee statue every morning. This explains the animated chant I heard so many times during the few months I attended a high school named after him: Douglas Southall Freeman! The South’s gonna rise again! Saaaa-luu!

Where I now live in Jacksonville, Florida, I’ve encountered this reverence for both Freeman and Lee—the version of Lee passed down through Freeman’s biography—in the small Museum of Southern History and in a memorabilia shop called Uncle Davey’s Americana, each one a shrine to the Confederacy (stories on these to come one day, too). Indeed I heard all about Freeman’s big salute as first editions of the biography were proudly pointed out in the collections at each location. Before my trip to Richmond this summer, Dave Nelson—the keeper of Uncle Davey’s Americana and a transplanted Richmonder himself—told me that he understands why academic historians disregard Freeman’s book but that he still chooses to believe in the character of Lee it depicts. A man of Freeman’s acumen wouldn’t have written such a laudatory biography had his subject not been fundamentally righteous, and such dedication to Lee’s supposed good character is likewise proof of Freeman’s discernment. Something like that. For people who want to believe in the whole Confederate lie, the salute story somehow closes a circle of truth comprising the biographer, the biographical subject, and the prize-winning biography.

highly decorated

Now all the Confederate statues along Monument Avenue are gone, along with some others around the city. The Lee statue was the first to rise in 1890, and due to some legal disputes it was the last to come down, 131 years later in September of 2021.

Another was the statue of J.E.B. Stuart at the Stuart Circle intersection. The Richmond Times-Dispatch created an excellent photo gallery showing the monument from its unveiling in 1907 through the protests and removal on July 7, 2020. As with all of this, photos show both the offending monument and the architectural beauty of the neighborhood it stood in for over a century.

The two images below capture the city’s changing story well. In one, taken during the removal process, the layers of public messages decorating the pedestal don’t seem to say anything about Stuart himself, but focus on state-sponsored violence against Black Americans today. The monument’s new text read, “Hands Up. Don’t Shoot!”—“Black Lives Matter”—”Fuck Trump.” It’s such a good reminder about why taking these monuments down really mattered—because any image, or any person in power, sanctioning the old war to preserve slavery is a continuing threat to the safety of Black bodies. As one message covered by a few others more succinctly explained it, “HERE’S UR CONTEXT.”

A 1953 photo shows another side of the Stuart monument story, physically and temporally (yes, there are two beautiful churches at that intersection). Third graders from the Collegiate School for Girls ”decorated” the monument with Confederate flags on Memorial Day. My stepmother attended that school at the time, and so did I thirty years later. In the 80s, we still had to wear skirts and dresses every day, and we learned to hold on to the end of a sheet and skip around a may pole—as one does—and we participated in a dark, elaborate Christmas pageant every year, but at least we weren’t being taken on field trips doing this shit anymore!

For many people living now, the 113-year tenure of the Stuart monument may have created a sense of inevitability, an always-already-thereness. But the city itself can remember when it wasn’t there. It cast its shadow in that intersection for about 40% of Richmond’s story since its founding in 1737, and less than that when you consider how long the community that became Richmond existed before then. Even the Lee monument stood for less than half the city’s current age. Every passing year shrinks the Confederate occupation to a smaller chapter in Richmond’s story.

from Stuart to Obama

The recent monument removals align with Richmond’s dedication to changing its problematic and hurtful school names. According to an article in Education Week, this academic year the city changed its four remaining Confederate-associated school names, making Richmond the nation’s city with the most name changes and Virginia the state with the most.

In the immediate area, the school board of neighboring Hanover County voted to change the name of Lee-Davis High to Mechanicsville High in 2020, whereas in 2019 Richmond’s school board voted to close Robert E. Lee Elementary at 3101 Kensington Avenue due to high operating costs, low enrollment, and the need for extensive renovations to the 1919 building. The property is now an apartment building called River City Lofts. Jacksonville and San Antonio, Texas, used some common strategies to get rid of their Robert E. Lee problems: in Jacksonville, the school was renamed after its Riverside neighborhood, while San Antonio repurposed the initials to stand for Legacy of Educational Excellence (LEE).

As an adult, I lived in the Fan district near what was still Robert E. Lee Elementary, and my first home was in the nearby Highland Park and Ginter Park area where my dad grew up in Richmond’s Northside. While in Richmond this summer, I drove around those Northside neighborhoods and visited the school on Fendall Avenue that used to be called J.E.B. Stuart Elementary. But in 2018, the school board voted to rename it after Barack Obama.

The main page on the school’s website now says “Welcome to Barack Obama Elementary! We Love You Here,” right above a link to “learn more about” the school’s history. Perhaps anticipating the you-can’t-erase-history crowd, a slideshow reviews the school’s timeline. At the end, teachers are shown in t-shirts that say “From Stuart to Obama, 1922-2022.” There’s no effort to forget the school’s founding in 1922, when its name was a nod to the Lost Cause. As the link suggests, the history is still right there to learn.

When Stuart gave way to Obama, I bought a $25 fundraiser t-shirt. I wore that shirt to a “Take ‘Em Down” event at what used to be called Confederate Park here in Jacksonville. That event illuminated the continuing problem of Confederate monuments and reminded the public, again, that maintaining slavery was the reason for secession and not the spurious “states’ rights” narrative. Just a few weeks ago on December 27th, I joined some of the same friends in the same space, which has since been renamed Springfield Park, to witness the removal of a large monument entitled “In Memory of Our Women of the Southland,” sometimes referred to as Confederate Mother. My friend Tim Gilmore wrote a great story about the monument and the removal which you can read here. There was so much resistance in Jacksonville that the new mayor Donna Deegan arranged to cover it with private funds, and some members of the local rearguard are still trying to drum up a problem with the way it was handled. Some want to see their reminder of the old racial order restored.

a school for white moderates

The story of Richmond’s monument removals and school renamings is, just as in Jacksonville, a slow roll in the right direction that will probably continue. But there is some very noticeable work to do in Richmond’s immediate environs.

Until the city was independently incorporated in 1842, Richmond was the seat of Henrico County. The county borders the city on three sides, and they are, for residents, one big place. When a new high school was built in 1954 not too far over the imperceptible county line, it was named after Douglas Southall Freeman. Born too late to fight for the Confederacy or enslave anyone, Freeman carried that flag forward as an apologist, a segregationist, and a proponent of eugenics. His public ideas about race were shared by many of the region’s white residents and readers of the News Leader. The new high school’s name and its “Rebel” mascot supported and still support the false narrative they wanted to hear, not just about the Civil War, but about white supremacy.

The school’s opening came about a year after Freeman’s death, and a few months after the Brown v. Board decision. The student body was 100% white at that time, but the possibility of integration was more real than ever. Many schools in the counties surrounding Richmond—such as the aforementioned Lee-Davis High School—opened in the mid-1950s amidst former Virginia governor and US senator Harry Flood Byrd Sr.’s (1887-1966) Massive Resistance plan. Through various means, legislators, school boards, and racist organizations worked to undermine and resist federal integration orders. As was typical across the South, it would take nearly ten years before Richmond schools began to comply with Brown.

Schools across the area have changed their names, but Freeman is still Freeman. Obviously I am not the first to notice this problem, nor the first to champion Planet editor John Mitchell as a replacement. In June of 2020, one of the school’s graduates named Nathan Thomson published a short opinion piece in the Richmond Times-Dispatch reminding readers of the problematic association and suggesting the school be renamed after Mitchell. Also in 2020, theVirginia Mercury published a more detailed reflection by another Freeman graduate. Beau Cribbs indicts his own former lack of engagement and asks other white people not to sit so comfortably in the role Martin Luther King, Jr. warned would be the most difficult barrier to racial progress: the “white moderate.”

Such “moderation” was displayed in what seems like a half measure in 2020. While keeping its name, the school changed its mascot from the Rebels to the Mavericks. At the time, school principal John Marshall spoke about “building the most inclusive school we can” and “becoming a leader in culturally responsive and anti-racist education.” The Principal’s Message on the school’s website again expresses support for “a school that unites and uplifts our community.”

Part of that uplift surely needs to include telling the truth. If there is anything on the school’s website to acknowledge the facts about its namesake, I couldn’t find it. This “polite silence” rings out. Freeman’s position as a favorite son has been hard to shake, but the local public narrative should surely also emphasize his role in spreading Lost Cause ideology. Turning the other cheek to Freeman’s offenses risks condoning his ideas—this especially matters because these are not just some unfortunate aspects of a story we’ve left behind. Segregationists and would-be eugenicists never went away, and they are gathering steam in Trump’s America.

Almost 70 years after Mitchell editorialized about liberal whites showing up with too little and too late, MLK's 1963 "Letter from Birmingham Jail" identified a similar problem in the white moderate who sits too much on the sidelines when the work to do is plain. The people in Richmond and Henrico County apparently have not yet exerted enough pressure to get this problematic name changed. One wonders which parts of the story the public still need to hear before agreeing that Freeman’s successes—many of which are dubious anyway—don’t make up for his dedication to vile ideologies.

“there to take it down”

Freeman’s favorite statue was standing for a while after the rest had been removed, but it did come down. And it happened just as John L. Mitchell, Jr. said it would.

In the May 31, 1890 Planet, Mitchell described that week’s grand parade to welcome Monument Avenue’s first Confederate statue. Along with the horde of Confederate sympathizers clogging city streets, he noted “Rebel flags were everywhere”:

These emblems of the “Lost Cause,” many of which had been perforated by Union bullets, were carried with an enthusiasm that astounded many. . . . The South may revere the memory of its chieftains. It takes the wrong steps in doing so, and proceeds to go too far in every similar celebration.

Even City Hall, Mitchell reported, was draped with a huge Confederate flag. His description of the day is distressing. But the next issue—though retaining his signature bitterness toward a nation that wasn’t catching up fast enough—takes a longer view of Black Richmonders’ role in writing the city’s story:

The Negro was in the Northern processions on Decoration Day and in the Southern ones, if only to carry buckets of ice-water. He put up the Lee Monument, and should the time come, he will be there to take it down. He’s black and sometimes greasy, but who could live with out the Negro?

Mitchell predicted one of the most important recent episodes in Richmond’s story 131 years before it happened. A Black-owned company contracted to remove the monuments was “there to take it down,” and Channel 13’s video from September 8, 2021 shows an African American man strapping the old bastard up for one last ride. The city turned many of the statues over to the Museum of Black History and Culture, now housed in the Leigh Street Armory building. This building housed the country’s first armory for an all-Black militia, and not surprisingly Mitchell contributed to that 1895 decision through his journalism.

The take-down of Robert E. Lee himself across Richmond seems pretty much complete, but the journalist who did so much to maintain the general’s reputation remains on a school. Some time back, theTimes-Dispatch issued an apology for the way its sister paper the News Leader supported eugenics under Freeman’s control. In 2022, the University of Richmond finally agreed to fully remove Freeman’s name from one of its dormitories—but only after an outrageous “both sides” attempt that saw the building named Mitchell-Freeman (!) for a period in 2021. The building’s current name—Residence Hall No. 3—certainly doesn’t sanction white supremacy (unless vanilla counts), but it doesn’t do much to remediate the school’s long allegiance to Freeman. At this time, the school’s housing website does a good job explaining the reasons for adding Mitchell’s name a few years ago. The university does not explain why Mitchell could not remain after Freeman was—at long last—abandoned, but it looks like a permanent decision is still in progress.

As the city’s private university begins—but slowly—to turn this page, perhaps it can also be time for the large public high school down the road to stop honoring Douglas Southall Freeman and lift up the perspective of a very different Richmond chronicler. Mitchell’s 1890 words about the Lee statue apply just as well today when we think of the Lee apologist:

The South may revere the memory of its chieftains. It takes the wrong steps in doing so . . .

John L. Mitchell, Jr. sure knew some things about this city. And it’s not clear why kids should still be spending time under the banner of Freeman, a man whose reputation contributed to and depends on one of the nation’s most enduring and damaging false narratives. Just take him down already.

Love reading you. It’s so helpful in giving hard facts and honest history to fill in the blurry spaces of my own foundational beliefs. There’s a memory I’ve always had of a field trip I took from Slidell to New Orleans when I was in middle school. We went to a historic home in the Quarter of some Lost Cause family. The only thing I remember was the guide pointing out a floral still life painting hung above the mantle. The guide explained that after the War, it was illegal to publicly express allegiance to the Confederacy and that agents from the Union would periodically crack down on the display of its flag. To get around this, families sympathetic to the Lost Cause would hang these paintings of red, white, and blue flowers that were arranged in the design of the Confederate flag. The remarkable part of all this was that I remember at the time the guide making the Union out to be the villain in this story and that the former owners of the home were like resistance fighters. Sadly, I remember feeling sorry for the family who lived there, forced to bend to will of their oppressors, but never giving up entirely. Today, I feel for my African American classmates who were there with me as well, some of whom were my friends. I want to say it was the Gallier House, but it may have been some other landmark I’ve since forgotten.

There's so much good stuff in here. (And thank you so much for the link to my story.) So strange and convoluted that message about inclusiveness at Freeman (almost as ironic as DSF's last name). That mention of Civil War history with "a preference for campaigns over social and political history" -- I've noticed so much of that with neo-Confeds. Even when the battle to change Lee High School's name here in Jax was happening, there were people saying the name should remain because Lee was a great general. Fine, but WTF does that have to do with anything? I love your contrasting the "always-already-thereness" with the city's own memory. Positively psychogeographic! Regarding the "white moderate" -- and city vs. county -- obviously Richmond's collective skin color has darkened over the years, a wonderful irony for this old capital of the CSA. With all the positive changes happening in Richmond, as I've said before, I can't help but see it as symbolic of something larger than this city. And Richmond is, obviously, an enormously symbolic city. I'd love to see it flourish by increasingly attracting progressive residents of every race and ethnicity. After all, the problem with referring to the problems of the South, meaning the Confederacy, or post-Confederacy, is that the South and the Confederate States of America are not one and the same. If the South "rises again," it will do so by finally putting a stake through the heart of the CSA.