History Catchup with Hillary, part 1

The Dinsmore Homestead in Boone County, Northern Kentucky

Thanks for visiting Narrative Nation!

This is where I’ll collect some thoughts and images from my exploration of places with emotional significance for many Americans. Stops include Civil War and Revolutionary War sites and museums; state parks and historic homes; historical associations; and memorabilia and gun shops. To get a better sense of the narratives attached to historic places and the events and people they might commemorate, I look at the signage, collect the literature, and talk to visitors, staff, guides, and rangers. And of course, I mine the gift shops! Other sites such as a religious theme park and a gun show will help me consider how ideas about the nation’s history influence current American fascinations.

Parts of these reflections will be incorporated into the book I am developing with the working title “Loads of Heresy”: Far Right Revisions of the American Narrative. For now these stories are drafts to help me think about what I’m seeing and hearing. I’ve taken a week away, but I have a lot more stops to discuss from Kentucky, West Virginia, and Virginia, as well as some material from South Georgia and North Florida.

This is the first of two posts about the presentation of enslavement, Underground Railroad history, and African American lives after emancipation in Boone County, Kentucky. The second part includes the inspiration for Toni Morrison’s novel Beloved.

In the middle of June, I had an awesome Tuesday with my longtime fabulous friend, Hillary Deitz Delaney. This is one of two posts about what Hillary showed me when I asked about the public narrative in her storied corner of the nation.

Hillary lives in an area called Sugartit, a hamlet of the city of Florence in Boone County, Kentucky. This is the northern tip of the state. From Sugartit, it’s only a short drive to the Ohio River and across to Cincinnati. Before the Civil War, crossing the river from Kentucky into Ohio meant crossing from a slave state into a free state, so the Underground Railroad history is rich in this area.

I arrived at the Delaneys’ house Monday afternoon, and we all talked until bedtime. It was restorative to be with an old friend, see her husband Mike after many years, meet her son again as an adult, and shamelessly try to ingratiate myself with the cat called Flapjack and their 130-pound pup Jed.

In the morning, Hillary cooked a regional specialty called Glier’s Goetta for breakfast, and we headed over to the Boone County Borderlands Archive and History Center at Boone County Public Library. The center is in nearby Burlington. Hillary works there as Lead Researcher for African-American Initiatives; much of her work focuses on the extensive Underground Railroad history in that area and reconstructing African American family histories.

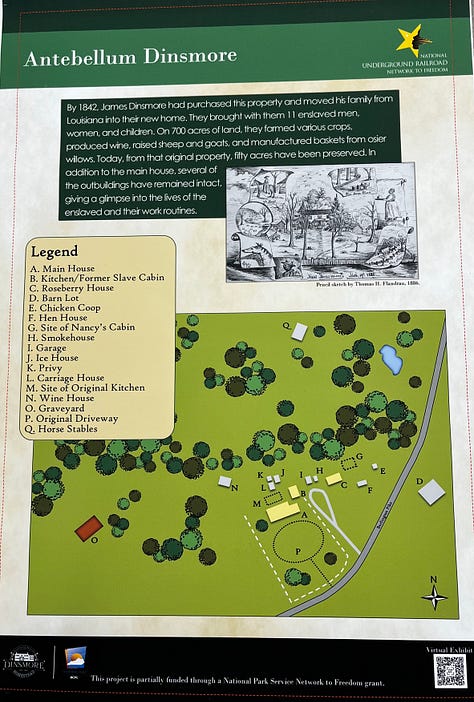

At the archive, I met the center’s director, Bridget Striker, and public history specialist Liza Pruiksma. Liza has recently completed a series of panels about the Dinsmore Homestead, an 1842 site on the National Register of Historic Places.

These panels, which will be seen by the public in the interpretive exhibit on site as well as a virtual exhibit, make the African-American history at Dinsmore more visible and accessible to visitors. They discuss the lives, work, and burials of those enslaved at the Homestead, along with some stories about post-enslavement life for African-Americans associated with that site. The work involved in sharing this more inclusive history of the Dinsmore property was funded by a Network to Freedom grant from the National Parks Service and by the Boone County Public Library.

James Dinsmore bought about 700 acres in Boone County and had the house built in 1842. Some of the enslaved people living at Dinsmore were brought there with the Dinsmores from Louisiana.

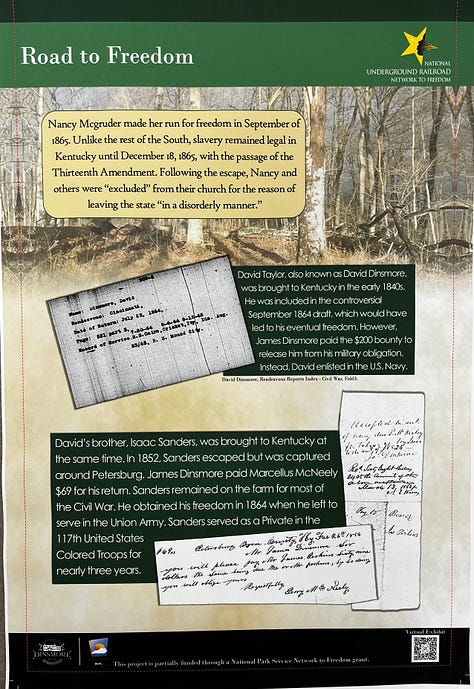

One panel tells of Isaac Sanders, an enslaved man who escaped in 1852 but was captured before he reached the Ohio River. James Dinsmore paid $69 to have him returned. When I asked Hillary if Isaac had been assisted by the Underground Railroad, she noted that direct records of an UGRR contact have not surfaced, but we can’t be sure: “he didn't have a chance to ‘board the railroad’ as it were, since he was captured on Kentucky soil.” Twelve years later, Sanders obtained freedom by another means when he joined the Union army in 1864.

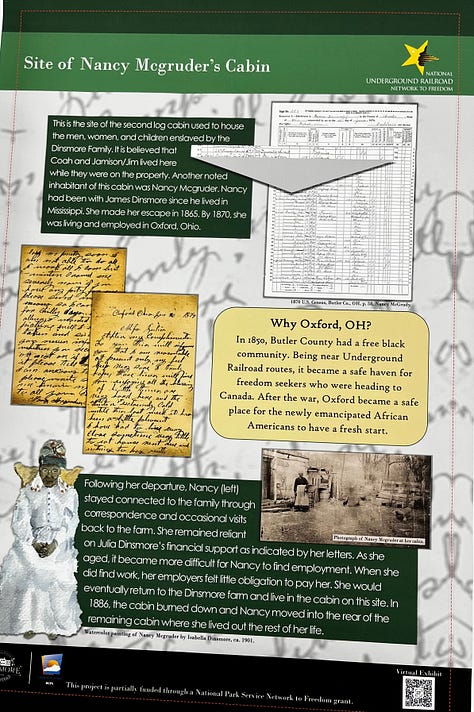

On other panels, the story of the enslaved, escaped, and later freed woman Nancy Mcgruder (~1810-1906) reveals the complexity of African American life as the Civil War was ending and in the years afterwards. Mcgruder, native to Virginia, had been purchased by James Dinsmore at about the age of 15 and was enslaved in Mississippi and then in Louisiana prior to being relocated with the Dinsmores to Kentucky. After more than 20 years at the Homestead, and only a few months before the national emancipation, Mcgruder left the farm without permission—what Hillary termed a “self-emancipation.”

Hillary explained in an email,

Nancy left in September 1865, when many enslavers didn't bother to even attempt to recapture enslaved people, since the question of enslavement had been answered by the outcome of the Civil War. But slavery was firmly in place when Nancy fled the Dinsmore farm. . . . [and] many Kentucky enslavers were still following the practice until the 13th Amendment was formally adopted to the Constitution on December 18th, 1865.

Mcgruder was not pursued by the Dinsmore family during these transitional months. Eventually she landed in Oxford, Ohio, where she lived with a white family as a domestic servant. A small community of free blacks had existed in Oxford since around 1850, and this became a popular place for the formerly enslaved to safely restart their lives after emancipation. Others from Boone County also resettled in Oxford, though many others emancipated from Dinsmore moved to a partially integrated Indiana community called Rising Sun.

I took this short video looking across the Ohio River from the settlement called Rabbit Hash in Kentucky to Rising Sun. It was not difficult to cross the river here, even when it wasn’t frozen.

Though Mcgruder maintained a substantive relationship with the Dinsmore family, this was at least in part due to necessity. Liza’s interpretive panel includes this glimpse into the challenges of post-emancipation life for some previously enslaved people:

Following her departure, Nancy stayed connected to the family through correspondence and occasional visits back to the farm. She remained dependent on Julia Dinsmore's financial support as indicated by her letters. As she aged, it became more difficult for Nancy to find employment. When she did find work, her employers felt little obligation to pay her. She would eventually return to the Dinsmore farm [in 1879] and live in the cabin on this site. In 1886, the cabin burned down, and Nancy moved into the rear of the remaining cabin where she lived out the rest of her life.

These aspects of Nancy Mcgruder’s life are well documented through letters, journals, and extensive household records preserved by James Dinsmore’s daughter Julia, who inherited the Homestead and managed more than 350 acres for decades after her father’s death in 1872. Some of the surviving letters are from Nancy, who was presumably taught to read and write by the Dinsmores. Julia even painted a watercolor of Nancy, depicted on one of Liza’s panels.

After leaving the Archive and History Center that morning, Hillary and I took a few hours to tour the area, of course including the Dinsmore Homestead. The mildly treacherous drive took us through the beautiful dark green North Kentucky hills down miles of roads winding, slanting, and steep. We were both glad Hillary was doing the driving. One of the documentaries I watched noted that Dinsmore bought so much property in that area because hills were cheap.

The Dinsmore House stands in its original location along Burlington Pike in Boone County. About fifty of Dinsmore’s 700 acres have been preserved. Still standing today are the 1842 Greek revival house and a number of smaller structures such as a log cook house that was originally a slave cabin, the ice house and privy, the wine house, and a four-room cottage. From the small cemetery just up the hill behind the house, the Ohio River and the state of Indiana are visible.

Standing to the right of the main house is the Roseberry House. This structure is another part of the African American history at Dinsmore and recently the focus of some important questions about the ways African American labor and tenancy might relate to inheritance rights down the line. Harry Roseberry (1881-1970) and his wife Sussie (d. 1941) were employed by Julia Dinsmore and lived on the property for decades. As their family grew to include four daughters, Harry built several rooms onto what was originally a single-room office made for Julia.

Roseberry descendants wanted to establish ownership of the cottage based on Harry’s labor and long tenancy. Since the materials were purchased by the Dinsmores and the structure stands on their land, it’s been determined to be part of the Dinsmore inheritance. Still, Harry’s descendants hope to see their family’s story told more respectfully, in part through the public presentation of the house their ancestor built. The building is now being used as an office, though descendants are involved in the planning to transform it into a proper part of the Dinsmore museum.

Many details from the stories of Nancy Mcgruder, the Roseberrys, Isaac Sanders, and numerous other African Americans associated with Dinsmore are included in documentaries from the state of Kentucky and the Behringer-Crawford Museum and through various educational programs produced by the Boone County Public Library. The Dinsmore Homestead website contains biographies of the enslaved and numerous servants and tenants after the war.

My initial goal in writing this story was not to share these unusually well-documented individual narratives in detail, though they are so interesting that I keep reading and watching more about them, and I can’t help but think they’re worth telling again. My real purpose is to examine the way this part of American history is being shared with the public at the site. While in this case the information about African American life at Dinsmore is already available online, real and transformative progress is made by the addition of such interpretive signage on site.

Unfortunately, the roadside marker on Burlington Pike says extremely little about the people enslaved there or the continuation of African American life on that property after the war. One side lists the commodities produced by “tenants and slaves” and by “German immigrants” without mentioning how many African Americans lived there and without naming Nancy Mcgruder or the Roseberrys.

A marker can only include so much, I understand, but noticing that Julia Dinsmore “became a published poet in 1910” instead of saying a bit more about the numerous African American residents seems almost glibly imbalanced. I would say this marker, sponsored by the Boone County Historical Society in 2014, needs an update. Perhaps this is a place the legacy of Harry and Sussie Roseberry could enter the public narrative. From the road where this marker was placed, both structures—the large Dinsmore House and the smaller Roseberry House—are visible, after all.

Excepting the lame roadside marker, this public history location feels like it’s about to be very different from what I observed at Andrew Jackson’s Hermitage in Nashville. At that site, I came away feeling that the African American history was not foregrounded enough and that visitors could too easily tour the place with very little exposure to the lives of the vast majority of people who lived and worked there.

In our follow-up conversations, Hillary explained that the new Dinsmore interpretive panels are only one “part of a bigger effort to reframe the history of that property.” Additional funds for what Director Bridget Striker called “initiatives to update Dinsmore’s enslavement narrative” came from a local government grant to change the National Register of Historic Places nomination form to include the enslavement narrative. Recently, African American board members have been appointed to the Dinsmore Foundation, including Dr. Eric Jackson, previous Director of African American Studies and now an associate dean at Northern Kentucky University, and Linda Thomas, a descendent of Harry Roseberry.

Looking ahead, the new interpretive panels produced by the Boone County Public Library will change the experience of every visitor to the Homestead. The property draws a lot of people interested in the Dinsmore family’s connections to several presidents and other influential white Americans, or in the life of the accomplished, somewhat unconventional, and long-lived community fixture Julia Dinsmore. Now those visitors will more readily see that story in its proper context: a very interesting family, but also a family whose privilege and lifestyle were made possible by the enslavement and tenant labor of black Americans.

Food tourism!

Lunch was another local standard: Skyline Chili, 5-way. For those who don’t know about Cincinnati Chili, it’s spaghetti noodles topped with chili and a fluffy mountain of shredded cheddar cheese. That’s the first three ways—those who go for all five get chopped raw onions and pinto beans. And of course a little ramekin of oyster crackers. This mild chili isn’t the more common TexMex style, but is instead more like a meat sauce with some Mediterranean spices like cinnamon. It was invented in 1922 by two Greek immigrants, brothers Tom and John Kiradjieff and first served at the Empress burlesque theater in downtown Cincinnati. My kids have been eating my version at home for years. Don’t worry, we got the small and a Greek salad.

The second part of this Boone County story features Margaret Garner, the woman whose life inspired Toni Morrison’s novel Beloved.

Then I have a fun-but-disturbing story about my four hours inside The Creation Museum—lots of pictures with that one! Prepare to Believe.

I'm not sure I can contribute much in my comments without risking giving away information that may be included in your upcoming posts! I encourage anyone interested in what we do at the Boone County Borderlands Archive and History Center to click the link and dig in!!